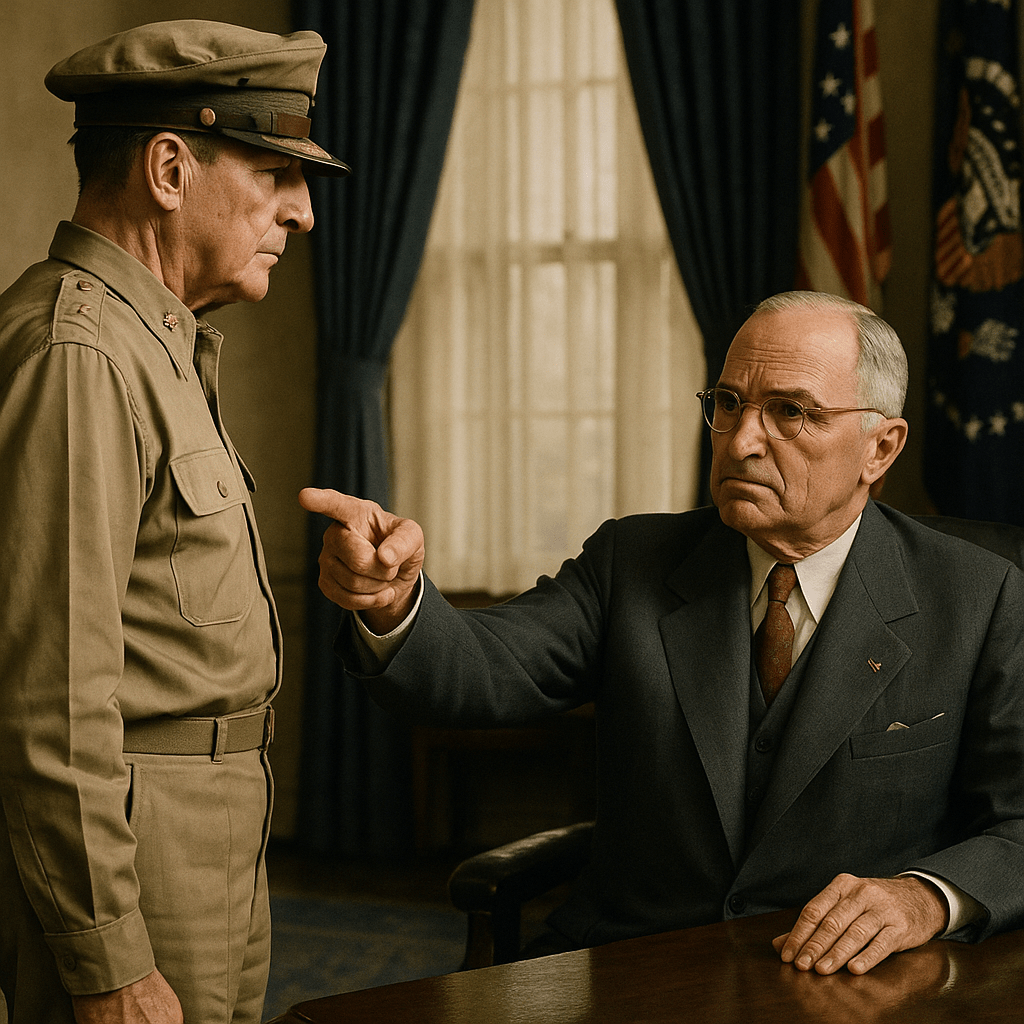

The General and the President

In the wake of World War II, America stood on the world stage as a superpower, but peace proved elusive. The Cold War was dawning, the atomic age had begun, and ideology—not armies—was now the battleground. In the middle of this shifting landscape stood two towering American figures: President Harry S. Truman and General Douglas MacArthur.

Truman was a no-nonsense, unpretentious man. A former haberdasher from Missouri, he had risen to the presidency after Franklin D. Roosevelt’s death and carried the enormous weight of ending the war in the Pacific by authorizing the use of atomic bombs. He didn’t crave the spotlight, but he had a steel backbone when it came to duty and the Constitution.

MacArthur, on the other hand, was the embodiment of military grandeur. With his corn-cob pipe, aviator sunglasses, and swaggering gait, he cut a dramatic figure wherever he went. He was a war hero many times over—decorated in World War I, the architect of victory in the Pacific during WWII, and the supreme commander of the Allied occupation of Japan. He viewed himself as a modern Caesar.

These two men were bound to clash. The only question was when.

The Seeds of Conflict

The Korean War broke out in June 1950 when North Korean troops, backed by the Soviet Union, launched a surprise invasion of South Korea. Truman, seeing it as a test of Western resolve against communist expansion, committed U.S. forces under the banner of the United Nations. And for this mission, he turned once again to his most experienced general—Douglas MacArthur.

At first, it looked like MacArthur might single-handedly win the war. After an early retreat by U.S. and South Korean forces to the Pusan Perimeter, MacArthur launched an audacious amphibious assault at Inchon in September 1950. It was a masterpiece of military strategy. The North Korean forces were caught off guard and thrown into retreat.

Flushed with victory, MacArthur urged Truman to let him pursue the North Koreans all the way to the Yalu River, on the border of China. Truman agreed—cautiously. He feared Chinese intervention but allowed the advance, hoping for a quick end to the war.

But MacArthur didn’t just want to win the war—he wanted to end communism in Asia. As UN forces pushed deeper into North Korea, China warned it would enter the conflict if the U.S. crossed the Yalu. MacArthur dismissed the threat. He believed Chinese forces were ill-equipped and wouldn’t dare confront American power.

He was wrong.

In November 1950, hundreds of thousands of Chinese troops poured into Korea. UN forces were overwhelmed and forced into a long, brutal retreat. What had seemed like imminent victory turned into a grinding stalemate. And now, the cracks between MacArthur and Truman split wide open.

A War of Words

The Korean War had become a political powder keg. Truman, having just survived the Berlin Airlift and the communist victory in China, was determined not to escalate the conflict into another world war. He believed the war in Korea should be contained—a limited war with limited goals.

MacArthur scoffed at the idea. He believed in total war, in achieving nothing less than unconditional surrender. And he wasn’t shy about saying so—publicly. This was where he crossed the line.

Despite Truman’s explicit instructions, MacArthur began making statements to the press that contradicted administration policy. He hinted at bombing Chinese bases in Manchuria, suggested blockading China’s coast, and even floated the use of nuclear weapons.

In March 1951, MacArthur went even further. He wrote a letter to Republican House Minority Leader Joe Martin, which was read aloud in Congress. In it, MacArthur criticized Truman’s policy of limited war and declared, “There is no substitute for victory.” The implication was clear: Truman was weak, and MacArthur knew how to win.

Truman was furious. He saw the letter not just as insubordination but as an outright challenge to the authority of the presidency. For a sitting general to criticize his commander-in-chief in such a public way was unprecedented—and unacceptable.

The Firing Heard ’Round the World

On April 11, 1951, after months of mounting tension, Truman made one of the most explosive decisions in American political history: he fired General Douglas MacArthur.

The announcement sent shockwaves through the country. MacArthur had been revered since WWII. Firing him was like dethroning a war god. Protests erupted, angry telegrams flooded the White House, and newspaper editorials blasted Truman for sacking a hero.

MacArthur returned to the U.S. a conquering figure. He was greeted by ticker-tape parades and delivered a nationally televised speech to a joint session of Congress. With emotion and polish, he uttered the now-famous line: “Old soldiers never die, they just fade away.” Many thought he was positioning himself for a presidential run.

But Truman stood firm. He knew the political cost of firing MacArthur, but he believed the principle at stake was far greater. As he said privately, “I didn’t fire him because he was a dumb son of a bitch, although he was. I fired him because he wouldn’t respect the authority of the President.”

The Fallout

In the short term, Truman paid the price. His approval ratings plummeted. Calls for his impeachment rang out in Congress. But Truman never regretted the decision.

Behind closed doors, military leaders—including General Omar Bradley and General Dwight D. Eisenhower—quietly supported Truman. They agreed that MacArthur had become unmanageable and dangerously independent.

MacArthur, meanwhile, faded from political relevance. Despite the public adoration, his bid for higher office fizzled. He retired from public life, occasionally consulted on foreign policy, but never again held a position of power.

Historians would later come to view Truman’s decision as a defining moment in the preservation of American democracy. Civilian control over the military had been tested—and had prevailed.

Legacy of a Feud

The Truman-MacArthur conflict remains one of the most dramatic showdowns in American history. It was more than a personality clash. It was a constitutional crisis, a test of military loyalty, and a warning against the dangers of unchecked power.

The stakes were enormous. The world teetered on the edge of nuclear war, and Truman made the unpopular choice to step back. In doing so, he reminded the country—and the world—that no matter how decorated a general might be, the power of war and peace ultimately rests with the people and their elected leaders.

In that moment, Truman didn’t just fire a general—he reaffirmed the very foundation of American government.

Leave a comment