A General in Crisis

In the early days of the American Revolution, Benedict Arnold was nothing short of a rising star. Born in Norwich, Connecticut, in 1741, he had a tempestuous nature but undeniable military brilliance. His early exploits — capturing Fort Ticonderoga in 1775 alongside Ethan Allen, and his daring trek through the Maine wilderness to attack Quebec — were feats of daring that few could match. He fought like a man possessed, often leading charges himself, earning the fierce loyalty of his men.

But as the war dragged on, Arnold’s wounds — both physical and emotional — began to fester. After Saratoga, where his heroic charge helped clinch victory but left his leg shattered, Arnold received little reward. Instead of promotion, he faced accusations: embezzlement, profiteering, misuse of military supplies. Congress was fickle, politics brutal.

Philadelphia, where Arnold was appointed military governor in 1778, should have been a fresh start. Instead, it plunged him deeper into scandal. He lived lavishly, married the beautiful and Loyalist-leaning Peggy Shippen, and tangled with civilian leaders over everything from taxes to requisitions.

By 1779, Arnold nursed a dangerous grudge. He wrote in secret to the British high command, offering his services. America, he believed, had failed him — and he would return the favor.

John André: The Perfect Gentleman Spy

Major John André was the British officer every mother wanted her daughter to marry. Young, cultured, a gifted artist and poet, André had charmed New York society while conducting espionage under the nose of Washington’s army.

Born in London in 1750 to wealthy Swiss-French parents, André had the makings of a classic romantic figure. He spoke several languages, wrote poetry, and sketched beautiful landscapes. When he was captured early in the war during the failed invasion of Canada, he spent a year as a prisoner in Lancaster, Pennsylvania — and became wildly popular with local ladies.

After his release, André’s talents earned him a spot as head of British intelligence in America. It was an unusual post for someone so idealistic — espionage demanded guile and ruthlessness — but André took to it with a sense of gallant adventure.

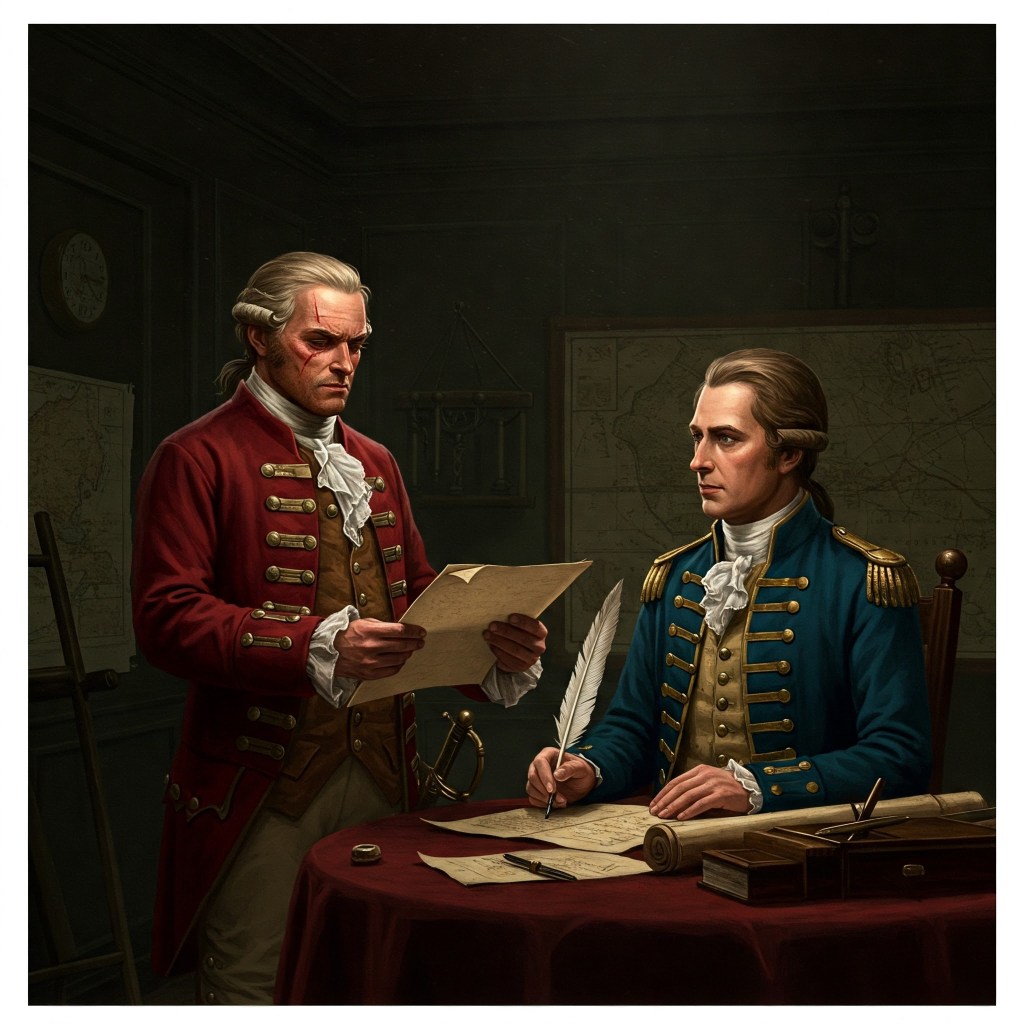

When the initial secret letters from “Gustavus” (Benedict Arnold) reached General Clinton in New York, André was the natural choice to answer. Skilled in invisible ink and code, he understood the delicate seduction of treason: offering flattery, promises of wealth, a place of honor.

The two men — the bitter, battle-scarred Arnold and the gallant, youthful André — were unlikely partners. Yet together, they would hatch one of the most infamous conspiracies in American history.

The Secret Plot: West Point for £20,000

As Arnold negotiated for his price, he chose his prize carefully. West Point, perched on the rocky banks of the Hudson River, was the single most important fortification in the colonies. It controlled river traffic — without it, the American cause could be strangled.

Arnold’s demands were bold: £20,000 and a commission in the British Army. (He later received far less — another injury to his pride.) In return, he would deliver West Point intact, complete with its garrison of about 3,000 soldiers.

To make the deception plausible, Arnold requested command of West Point from Washington himself. The general, trusting in Arnold’s previous heroism, agreed.

Over the summer of 1780, Arnold carefully weakened the fort’s defenses. He delayed repairs, spread out his forces dangerously thin, and stockpiled supplies in locations easily seized by a British assault.

As the day of betrayal neared, the risk grew greater. Letters crossed back and forth in invisible ink. Arnold’s young wife, Peggy, served as a courier, leveraging her old Loyalist contacts.

Finally, in September 1780, André and Arnold agreed: they would meet in person to finalize everything.

The Fateful Meeting: September 21, 1780

On the night of September 21, under a new moon, the British sloop Vulture crept up the Hudson. André went ashore in a small boat, rowed by a disloyal American sympathizer named Joshua Hett Smith.

The meeting took place under the shadow of a giant oak tree near Haverstraw. Arnold, ever paranoid, spent hours going over the plan in exhausting detail. He provided André with:

- Maps of West Point’s fortifications

- Notes on troop placements

- Passcodes for American outposts

Had the documents been delivered successfully, it could have spelled disaster for the American Revolution.

As dawn approached, disaster struck. American cannon fire from the riverbank, aimed at the Vulture, forced it to retreat downriver, cutting off André’s return. He was stranded.

Desperate, André agreed to cross American lines on foot, disguised in civilian clothes — a perilous journey without the protection of his British uniform.

Arnold gave him a pass to show at checkpoints, describing André as “John Anderson,” a civilian with permission to travel.

It was an audacious, foolish risk — and it would cost André his life.

The Capture of John André

Traveling south, André neared British-held territory when fate intervened. At Tarrytown, he was stopped by three armed American militiamen. André, flustered, initially thought they were Loyalists and revealed too much.

When searched, the secret papers hidden in his boot betrayed him.

Realizing the seriousness, André offered them his watch, gold, and promises of riches. But these rough countrymen — John Paulding, Isaac Van Wart, and David Williams — were too patriotic or too suspicious to accept.

He was marched to the nearest American command post. Arnold’s pass delayed suspicion briefly, but the discovery of West Point’s detailed blueprints and troop plans changed everything.

General George Washington, arriving at West Point shortly after, was stunned to find Arnold gone — he had fled aboard the Vulture after learning of André’s capture.

Trial and Execution

John André faced a grim tribunal. A board of senior American officers, including Nathanael Greene and Marquis de Lafayette, judged him not by his character, but by the rules of war: caught behind enemy lines, out of uniform, carrying secret papers — the classic definition of a spy.

Despite pleas for clemency, including from Washington’s own aides, the law was clear.

André comported himself with grace. He wrote touching letters home, thanked his captors for their courtesy, and faced his fate without flinching.

On October 2, 1780, at Tappan, New York, André was hanged. His last request — to die by firing squad like a soldier — was denied.

He met his death with quiet dignity. Soldiers and civilians alike wept.

Even Washington later admitted that André’s execution was a tragedy necessary for the preservation of order and discipline.

Meanwhile, Arnold — safe behind British lines — lived on, but as a man without a country.

Arnold’s Aftermath: A Man Without a Country

Arnold’s life after his betrayal was a long, ignominious decline.

Though granted a brigadier’s commission and some of his promised payment, Arnold was never fully trusted by the British. Fellow officers sneered behind his back. British Prime Minister Lord North himself considered Arnold “a bad bargain.”

Arnold led a few more raids, including the destruction of New London, Connecticut, in 1781 — an act of brutal reprisal that further blackened his name in America.

When the war ended, Arnold moved to London, where he tried unsuccessfully to win new military commands. He lived out his last years in relative obscurity, beset by debt and illness.

On his deathbed in 1801, Arnold reportedly asked to be buried in the uniform of the American Continental Army — a final, pitiful longing for the honor he had lost.

Thus ended the lives of the two men whose fatal friendship nearly brought down the Revolution.

Character Comparison: Benedict Arnold vs. John André

| Characteristic | Benedict Arnold | John André |

|---|---|---|

| Birth | 1741, Norwich, Connecticut, USA | 1750, London, England |

| Personality | Proud, combative, resentful, impulsive | Charming, artistic, idealistic, gallant |

| Role in Plot | Disaffected American general who betrayed West Point | British spymaster handling Arnold’s treason |

| Primary Motivation | Personal honor, resentment, financial gain | Duty to Britain, sense of adventure |

| Capture | Escaped to British ship Vulture | Captured near Tarrytown, New York |

| Fate | Lived out life disgraced in Britain | Executed by hanging in 1780 |

| Legacy | Synonymous with “traitor” in American lore | Romanticized as a tragic hero |

Sources:

- Flexner, James Thomas. The Traitor and the Spy: Benedict Arnold and John André (1953)

- Martin, James Kirby. Benedict Arnold: Revolutionary Hero: An American Warrior Reconsidered (1997)

- Randall, Willard Sterne. Benedict Arnold: Patriot and Traitor (1990)

- Van Doren, Carl. Secret History of the American Revolution (1941)

- Primary documents: Letters of Benedict Arnold to British authorities, 1780.

Leave a comment