Introduction – When Rome Thought It Had Found Its Golden Boy

Rome had been holding its breath. After years under the grim, reclusive Tiberius—who had spent much of his reign brooding on the island of Capri—the empire was starving for charisma, for charm, for a leader who looked and acted like a Caesar.

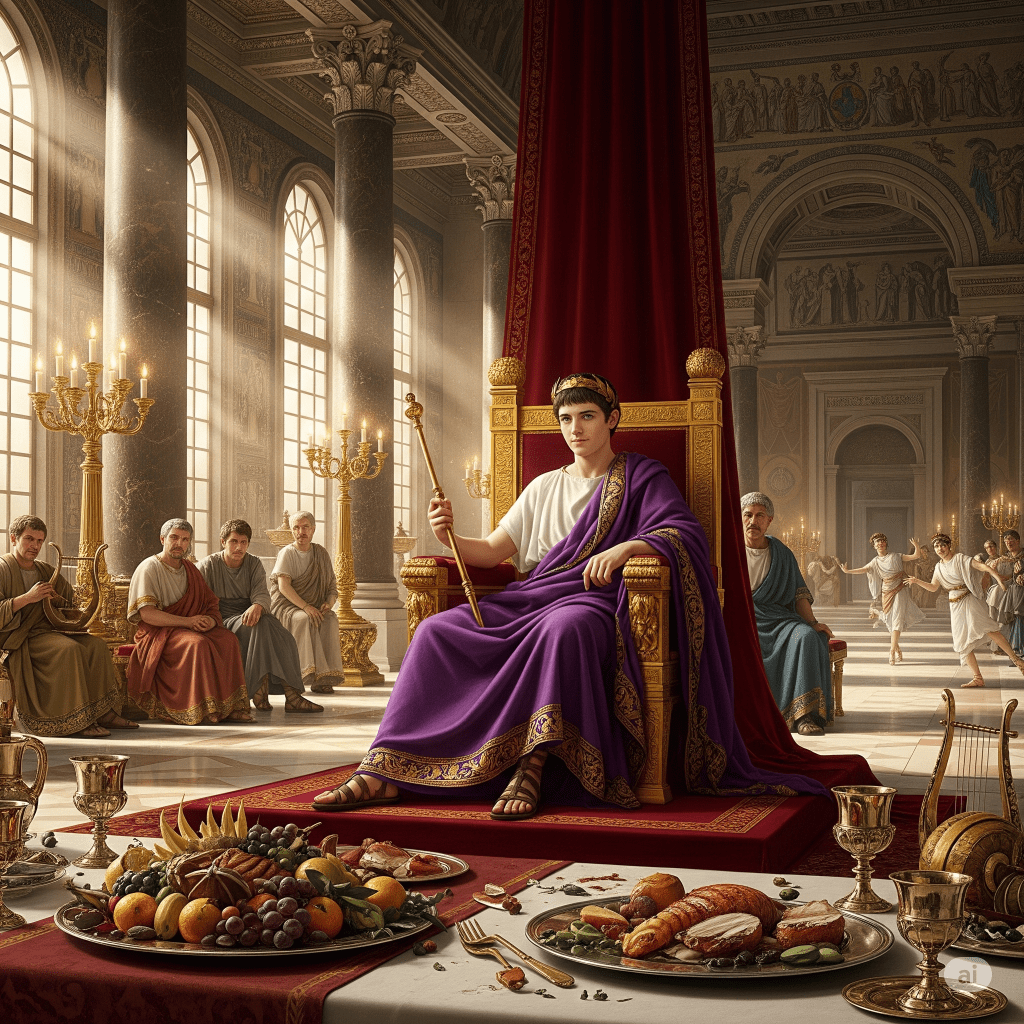

Enter Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, the son of the beloved general Germanicus. To soldiers who had seen him toddling around army camps in miniature soldier’s boots, he was “Caligula”—Little Boot. To the Roman people in 37 CE, he was the man destined to bring back the glory days of Augustus.

For a few shining months, it seemed they’d gotten exactly what they wanted.

But the shine didn’t last. Over the next 1,400 days—three years and ten months—Caligula’s reign would go from golden dawn to bloody nightmare, from cheers to daggers, in a way only Rome could produce.

The Honeymoon Phase – 37 CE

At first, Caligula was a dream come true. He freed political prisoners, recalled exiles, slashed unpopular taxes, and staged games so extravagant that even seasoned Romans were impressed.

When he entered the Forum, people climbed statues just to get a better view. The Senate declared a new age had begun. Suetonius wrote that the people thought “the heavens had opened and sent them a god in human form.”

But in October of that first year, the young emperor fell gravely ill. Ancient writers say it was fever; modern scholars suspect encephalitis, epilepsy, or even poisoning. He recovered physically… but politically and mentally? Many claimed something snapped.

The charming young ruler didn’t just change course—he floored the accelerator and yanked the wheel into oncoming traffic.

Clearing the Chessboard

Caligula had inherited the paranoid political machine of Tiberius—and he seemed to relish making it even deadlier.

First target? Macro, the Praetorian Prefect who had helped him to the throne. Macro and his wife were accused of treason and “invited” to take their own lives. Senators who hesitated to cheer him too loudly found themselves charged with plotting against the emperor.

Tacitus and Cassius Dio hint that many of these so-called plots were thin air, invented so Caligula could remove rivals and seize their fortunes. The message was loud and clear: loyalty wasn’t optional, and even loyalty yesterday didn’t guarantee safety today.

The Emperor as Showman

If there’s one thing Caligula loved more than power, it was spectacle. He didn’t just host gladiator games—he turned them into jaw-dropping, treasury-emptying events. Exotic animals fought in the arena. Actors recited poetry between bouts.

One year, Suetonius tells us, he burned through 2.7 billion sesterces—an amount that made even Rome’s famously wealthy elite gulp.

Some of his greatest hits included:

- The Floating Bridge at Baiae – Over two miles of boats lashed together across the Bay of Baiae, just so he could ride his horse across and thumb his nose at a prophecy that said he’d never be emperor.

- Banquets of the Absurd – Gold-flecked bread. Flamingo tongues. Pearls dissolved in vinegar. Guests left full… and dazzled.

- Marble and Jewels Everywhere – Palaces were redone in rare marbles, gems, and ivory, as if Rome’s architecture had to match the emperor’s ego.

But when the imperial piggy bank started looking light, Caligula found creative new ways to refill it—like taxing lawsuits, weddings, and even prostitution.

The God in the Palace

While Augustus had carefully avoided calling himself divine during his lifetime, Caligula dove into the role headfirst.

One day he was Apollo, the next he was Mercury, and sometimes—just to make jaws drop—he appeared dressed as Venus. He had his statue placed in temples and insisted sacrifices be made to it.

In Judea, he ordered that a massive golden statue of himself be erected inside the Temple of Jerusalem, an act so offensive to Jewish religious law it risked open revolt. (Only his assassination prevented it from happening.)

Philo of Alexandria and Cassius Dio leave little doubt—this wasn’t satire. Caligula really seemed to believe he was a living god.

The Horse and the Senate

And then… there’s Incitatus, the horse.

This was no ordinary steed. Incitatus had a marble stall, an ivory manger, purple blankets, and a jeweled collar. Suetonius claims Caligula planned to make him a consul, the highest elected official in Rome.

Was this sincere? Maybe not. It might have been a calculated insult to the Senate—Caligula’s way of saying, My horse could do your job better. Still, it became the story every schoolboy and historian would remember.

A Climate of Fear

By the last stretch of his reign, Caligula’s palace was less a court and more a minefield. People died for minor slights, whispered rumors, or simply owning something the emperor wanted.

Among the more infamous incidents:

- Having a nobleman executed simply for being handsome enough to draw attention.

- Forcing senators to run beside his chariot.

- Executing his cousin, Ptolemy of Mauretania, reportedly because Caligula liked his purple cloak.

Even the Praetorian Guard—his personal protectors—were mocked and insulted to their faces. They stayed loyal only as long as the donatives (cash bonuses) kept flowing.

The “Conquest” of the English Channel

In 40 CE, Caligula marched to the northern coast of Gaul, supposedly to invade Britain. The legions waited for orders to cross. Instead, Caligula commanded them to collect seashells as “spoils of the sea” and return to Rome.

Was it a failed invasion covered up with absurd theater? A symbolic military drill? Or was he genuinely trolling his own army? Historians still argue about it.

Whatever the truth, the episode added another brushstroke to the picture of Caligula as Rome’s mad emperor.

The Last Act – January 24, 41 CE

By early 41 CE, enemies were everywhere—especially in the palace itself. The leader of the plot was Cassius Chaerea, a Praetorian tribune whom Caligula had mocked for having a soft voice.

During a festival at the Palatine Games, Chaerea and a group of conspirators cornered Caligula in a tunnel beneath the theater. They stabbed him more than 30 times. His wife, Caesonia, and their young daughter were also murdered—just to erase any future claimants.

The man who had strutted as a god died on a dirty floor, bleeding out under the boots of his own guards.

The Cleanup – Erasing the Mad Emperor

In the chaos that followed, the Senate briefly toyed with restoring the Republic. The Praetorian Guard had other ideas. They found Caligula’s uncle, Claudius, hiding in the palace and proclaimed him emperor.

Then came the official condemnation—damnatio memoriae. Statues smashed. Names erased from inscriptions. Public records scrubbed. In the official narrative, Caligula was not just dead—he was to be forgotten.

But history, as always, had other plans.

The Verdict – Monster or Myth?

The 1,400-day reign of Caligula is one of the most infamous in Roman history.

Ancient sources—Suetonius, Cassius Dio, Josephus—paint him as cruel, unstable, and arrogant. Modern scholars point out that most of these writers were senators or court intellectuals with every reason to blacken his name after his death.

Some stories (like the seashells, or Incitatus as consul) may be true, exaggerated, or invented satire. But the core reality remains: Caligula’s reign left Rome with a cautionary tale about what happens when absolute power collides with absolute ego.

Conclusion – A Comet That Burned Too Bright

Caligula’s story is the Roman Empire at its most theatrical—glory, decadence, blood, and scandal in rapid succession.

For a brief, dazzling moment, he was the people’s champion. Then, faster than the Senate could draft new honorifics, he was their terror. Whether he was a lunatic, a satirist gone too far, or a victim of political spin, his 1,400 days on the throne remain a masterclass in how quickly a ruler can go from Hail Caesar to Death to the Tyrant.

Sources

- Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, “Caligula.”

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, Books 59–60.

- Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius.

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, Book 18.

- Barrett, Anthony A. Caligula: The Corruption of Power. Yale University Press, 1989.

Leave a comment