It was just before sundown on a humid Friday in June 1953, the Jewish Sabbath about to begin, when the switch was thrown twice in upstate New York—first for the husband, then for the wife—making them the first American civilians ever executed for espionage during peacetime.

But to understand how Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, a seemingly mundane couple from the Lower East Side with two young sons, ended up strapped into Sing Sing’s electric chair, we have to rewind past the hysterical headlines of the 1950s to a Los Alamos machine shop five years earlier, where a disgruntled brother-in-law was sketching secrets on a napkin.

The story of the Rosenbergs is a Cold War noir thriller that happens to be true. It’s a tale splashed with atomic secrets, family betrayal of biblical proportions, a hysterical nation looking for scapegoats, and a lingering question of whether justice was served, or merely vengeance.

The Atomic Jitters

To get the Rosenberg story, you have to get the vibe of America around 1950. The United States had just won World War II and felt pretty good about its global dominance, largely because it was the only kid on the block with the ultimate slingshot: the atomic bomb. Scientists estimated it would take the Soviet Union a decade to catch up.

Then, in August 1949, the Soviets successfully tested their own bomb, “Joe-1.”

America panicked. The timeline had shrunk from ten years to four. The conclusion wasn’t that Soviet scientists were smart; it was that American secrets had been stolen. The terrifying realization that the godless Commies suddenly had nuclear parity sent a voltage of fear through the political landscape.

This was the petri dish that grew Senator Joseph McCarthy, who waved lists of alleged communists in the State Department. The House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) was ruining Hollywood careers. Air raid sirens were tested in sleepy suburbs. The country was primed to find the villains responsible for bursting America’s nuclear bubble. They needed faces to put to the betrayal.

They found Julius and Ethel.

Just Your Average Radical Neighbors

On the surface, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were aggressively normal. Living in a modest apartment in Knickerbocker Village on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, they raised their two boys, Michael and Robert. Julius was an electrical engineer who struggled in business; Ethel was a promising singer and dedicated mother.

But beneath the domestic veneer beat the hearts of dedicated, hardcore communists. They hadn’t just flirted with Marxism during college; they were true believers who met at a Young Communist League fundraising drive in 1936. By the 1940s, during WWII when the Soviets were our allies against Hitler, Julius wanted to do more than just attend meetings. He wanted to help the “Motherland.”

Julius wasn’t James Bond. He didn’t wear tuxedos or drink martinis. He was an ideological foot soldier, an engineer who used his unremarkable appearance to run a spy ring of fellow sympathetic engineers, funneling industrial and military secrets to Soviet handlers.

He was enthusiastic, daring, and—as history would prove—dangerously amateurish.

The Dominoes Fall

The unraveling of the Rosenberg network didn’t start in New York; it started in London. In 1950, British intelligence cracked Klaus Fuchs, a brilliant physicist who worked on the Manhattan Project. Fuchs admitted to passing atomic research to the Soviets.

When you catch a spy, you squeeze them for their courier. Fuchs gave up Harry Gold, a sad-sack chemist in Philadelphia who acted as a go-between for Soviet intelligence.

The FBI squeezed Harry Gold. Gold remembered a specific pickup in Albuquerque, New Mexico, in 1945. He remembered a young soldier working at the Los Alamos National Laboratory, and he remembered the soldier’s wife. The breadcrumbs led straight to David Greenglass—Ethel Rosenberg’s younger brother.

And this is where the tragedy turns Shakespearean.

David Greenglass was a machinist at Los Alamos during the war. He wasn’t a high-level physicist, but he had access to the physical bomb components. When the FBI knocked on his door in 1950, David, terrified and looking at decades in prison, cracked.

He admitted that Julius Rosenberg, his own brother-in-law, had recruited him into the spy ring. He admitted to passing crude sketches of the bomb’s implosion lens to Julius. To verify their identity to the courier Harry Gold, Julius had cut the side of a Jell-O box in a jagged pattern, giving half to David and keeping half for the courier—a detail so folksy it could only be true.

But David had a problem. His wife, Ruth, had been deeply involved in the conspiracy. The FBI threatened to indict her, which would leave their own two children parents. To save his wife, David Greenglass offered up his sister.

David changed his initial testimony. He suddenly recalled a crucial detail: that Ethel Rosenberg was present during the espionage discussions and, most damningly, that she had typed up the handwritten notes about the atomic bomb on a Remington portable typewriter in their apartment.

That testimony was the nail in Ethel’s coffin. The government now had their “Atom Spy Ring” couple.

The Trial by Fire

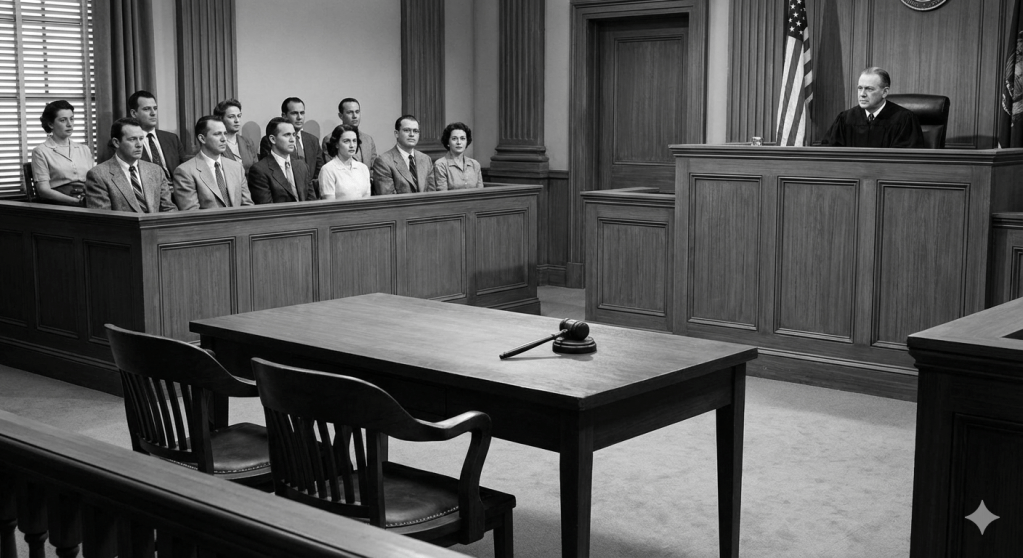

The trial began in March 1951 in New York’s Southern District federal court. It was less a legal proceeding and more a political exorcism.

The atmosphere inside the courtroom was poisonous. The Korean War was raging, pitting American troops against communist forces, heightening the stakes. The prosecution, led by the ambitious Irving Saypol and his ruthless young assistant, Roy Cohn (who would later become Joseph McCarthy’s right-hand man and, decades later, a mentor to Donald Trump), painted the Rosenbergs not just as spies, but as traitors responsible for future nuclear Armageddon.

The star witnesses were David and Ruth Greenglass. David, sweating on the stand, testified against the sister who had once bought him his clothes. He recounted the Jell-O box, the sketches, and Ethel’s typing.

The evidence against Julius was substantial, though entirely based on the testimony of co-conspirators who were cutting deals. The evidence against Ethel, however, was breathtakingly thin. It rested almost entirely on David’s “remembered” detail about the typing—testimony given to protect his own wife.

Julius and Ethel took the stand but refused to answer questions about their communist affiliations, pleading the Fifth Amendment repeatedly. In 1951 America, taking the Fifth was practically seen as a confession of guilt. They steadfastly maintained their innocence regarding espionage.

The defense was outmatched. The judge, Irving Kaufman, was deeply hostile to the defendants. He viewed their actions as a betrayal of both their country and their religion. The jury took a mere seven hours to convict Julius and Ethel of conspiracy to commit espionage.

Death House and Global Outcry

Under the Espionage Act of 1917, the judge had discretion in sentencing. He could give them prison time, or he could give them death.

On April 5, 1951, Judge Kaufman delivered a sentencing speech that still blisters the paint off history books. He blamed the Rosenbergs for the Korean War and future millions of deaths.

“I consider your crime worse than murder,” Kaufman thundered. He sentenced them both to die in the electric chair.

The severity of the sentence shocked many. Even J. Edgar Hoover, the bulldog head of the FBI, had only wanted Ethel getting significant prison time, hoping to use her as leverage to make Julius name his other contacts. Julius never broke. He refused to name names to save himself or his wife.

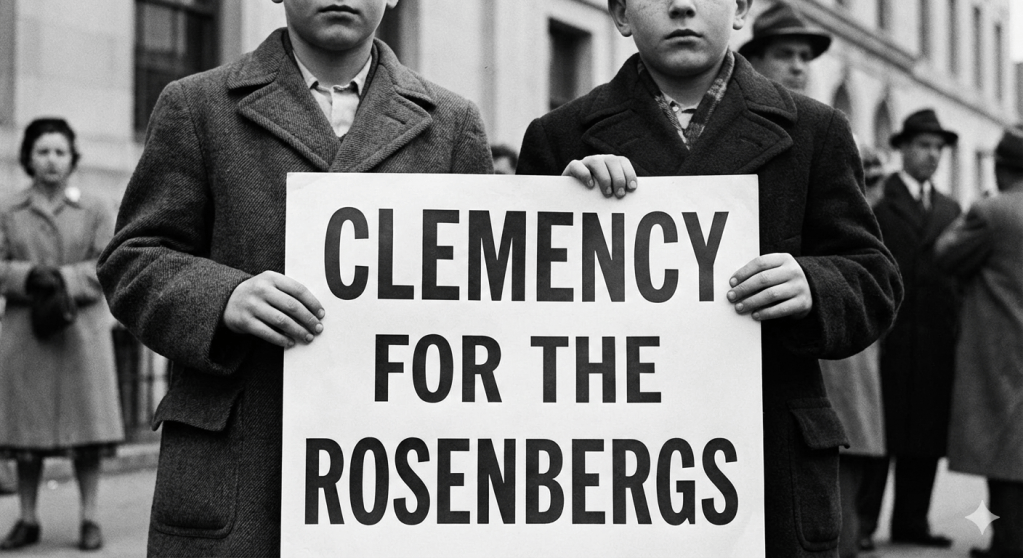

For two years, the couple languished on death row in Sing Sing prison. Their case became a global cause célèbre. The perception grew that they were being executed not for what they did, but for what they believed, and because the US government needed a scalp for the loss of the atomic monopoly.

Pope Pius XII appealed for clemency. Albert Einstein, Pablo Picasso, and Jean-Paul Sartre publicly condemned the sentence. Jean Cocteau called it “a human sacrifice to the god of the cold war.”

Their young sons, Michael and Robert, were marched to the White House gates to protest, holding signs begging for their parents’ lives. It was heart-wrenching theater, but newly elected President Dwight D. Eisenhower, a military man to his core, was unmoved. He denied executive clemency, stating their crime involved “the deliberate betrayal of the entire nation.”

On June 19, 1953, time ran out. Julius went first. He died quickly after the first jolt. Ethel’s execution was a grisly, botched affair. The initial shocks didn’t kill her; doctors found a heartbeat. They had to strap her back in and apply more current, smoke rising from her head, before she was pronounced dead.

Secrets Declassified: The Verdict of History

For decades after the execution, the American left maintained that the Rosenbergs were pure martyrs—totally innocent victims of a frame-up. The American right maintained they were atomic devils who single-handedly gave Stalin the bomb.

History, as it turns out, is messier than either side wanted to admit.

After the fall of the Soviet Union in the 1990s, the release of the “Venona project” intercepts—decoded cables between Soviet spies and Moscow during WWII—changed everything.

The cables confirmed unequivocally that Julius Rosenberg was indeed a hardworking Soviet spy, codenamed “LIBERAL” and later “ANTENNA.” He ran a productive ring of engineers actively stealing military technology. He was guilty of espionage.

However, the cables also suggested that the atomic information Julius passed along (via David Greenglass) was crude and not critically important to the Soviet bomb project. The Soviets got the real goods from Klaus Fuchs and another spy at Los Alamos, Theodore Hall, whom the FBI never caught. Julius thought he was giving away the crown jewels; in reality, he was giving away costume jewelry.

And Ethel? The intercepts showed the Soviets knew she was aware of Julius’s work—they gave her a codename too—but they did not consider her an active operational spy.

The most devastating postscript came from David Greenglass himself. In December 2001, decades after his release from prison (he served nearly 10 years) and living under an assumed name, he admitted to a journalist that he had lied on the stand about Ethel typing the notes.

“I frankly think my wife did the typing, but I don’t remember,” Greenglass confessed, admitting he perjured himself to satisfy the prosecutors and save his wife. “I sacrificed my sister,” he said, with chilling nonchalance.

Why This Still Matters

The Rosenberg case remains an open wound in American history not because of the question of guilt—we know Julius was a spy—but because of the question of proportionality and the corruption of justice by fear.

They were the only two American civilians executed for espionage-related crimes during the entire Cold War. Other spies who did far more damage, like Klaus Fuchs, received prison sentences. The Rosenbergs received the ultimate penalty because they refused to cooperate in an era that demanded ideological submission.

The government, driven by political hysteria and the need to project strength, used a mother of two as a pawn to pressure her husband, and when that failed, executed her based on perjured testimony coerced by prosecutors.

Today, as we face renewed global tensions, fears of foreign influence, and debates over the balance between national security and civil liberties, the ghosts of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg still haunt the courthouse. Their story is a stark reminder of what happens when the justice system becomes a weapon in a political war, and how fear can make a nation justify the unjustifiable.

Sources:

- The Venona Project intercepted cables (National Security Agency declassified archives).

- “The Brother: The Untold Story of the Rosenberg Case” by Sam Roberts (containing the 2001 David Greenglass confession).

- “Final Verdict: What Really Happened in the Rosenberg Case” by Walter Schneir.

- FBI records on the Rosenberg/Greenglass case.

- Trial transcripts of United States v. Rosenberg.

Leave a comment