In the autumn of 312 AD, the fate of the Roman Empire hung in the balance. The ambitious Constantine, ruler of the western Roman Empire, stood at the threshold of war against his rival, Maxentius. Their battleground would be the Milvian Bridge, a vital crossing over the Tiber River leading into Rome.

Constantine was no stranger to battle, but this campaign was different. Maxentius had declared himself emperor in Rome and held the city with a powerful army. Despite being outnumbered, Constantine had pushed forward, winning skirmishes along the way. Yet on the eve of battle, uncertainty loomed. Would his forces prevail against an enemy fortified within the heart of the empire?

That evening, as the sun dipped behind the hills, Constantine pondered his fate. He had worshipped the traditional Roman gods for most of his life, but he had also heard of the Christians—an emerging group that spoke of one true God. His father, Constantius, had been sympathetic to them. Perhaps there was something to their faith.

Little did he know that the coming night would change his destiny—and the course of history—forever.

The Vision in the Sky

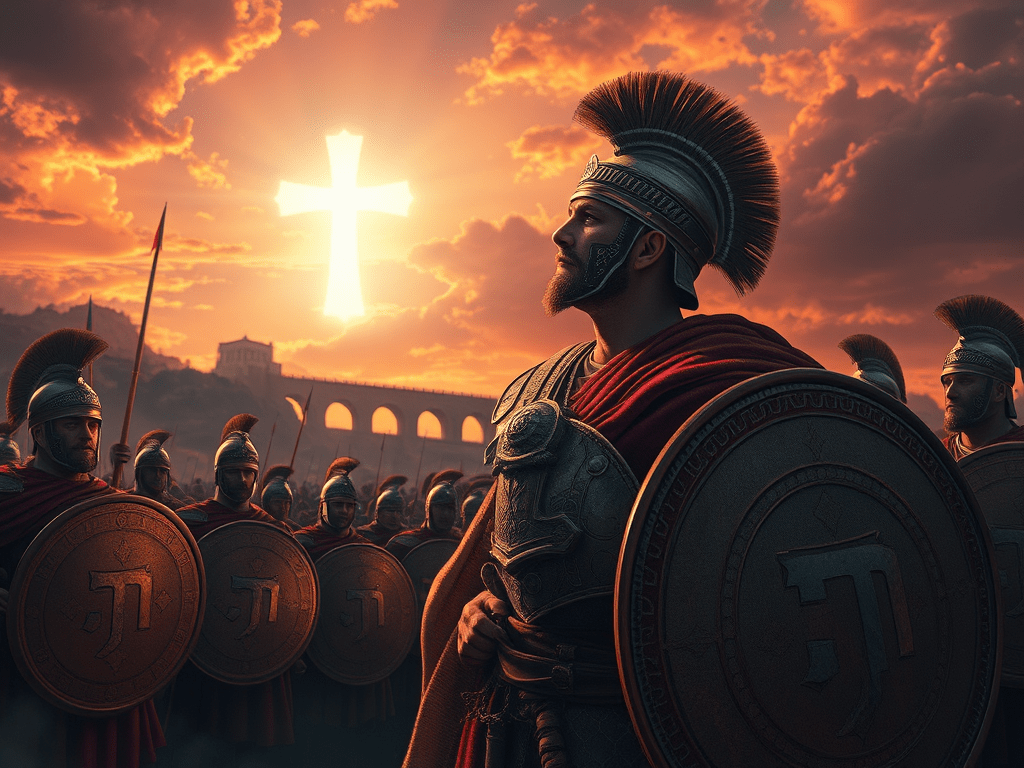

As the day faded, Constantine and his soldiers beheld an astonishing sight. According to contemporary accounts, including those of the Christian historian Eusebius and the pagan orator Lactantius, a brilliant cross appeared in the sky, shining brighter than the sun and accompanied by these words: “In hoc signo vinces”—”In this sign, conquer.”

The soldiers murmured in awe, pointing skyward. The image was unmistakable: a cross, the symbol of the persecuted Christian faith. Constantine, stunned, wrestled with its meaning. That night, he dreamed of a divine figure—Christ Himself—who instructed him to mark his soldiers’ shields with the Chi-Rho, the first two Greek letters of Christ’s name (ΧΡ). This would be his sign of victory.

Waking at dawn, Constantine wasted no time. He ordered his men to paint the Chi-Rho on their shields. While some were skeptical, they obeyed. Whether by divine favor or sheer belief in their leader’s vision, they marched to battle emboldened.

The Battle of the Milvian Bridge

On October 28, 312 AD, the forces of Constantine and Maxentius clashed at the Milvian Bridge. Maxentius, confident in his superior numbers, had taken a fateful decision: rather than remain behind Rome’s walls, he led his troops onto the battlefield, forcing an open confrontation.

Constantine’s army, bearing the Chi-Rho, fought fiercely. Despite being outnumbered, they pushed Maxentius’ forces back toward the river, then disaster struck. His troops, retreating in disarray, found the bridge bottlenecked. In the chaos, the bridge collapsed beneath them, and many drowned in the Tiber—including Maxentius himself.

It was a stunning victory. Constantine rode into Rome, welcomed by its people as the rightful emperor. The vision in the sky had proved true.

The Legacy of the Vision

Constantine’s vision was more than a personal revelation—it transformed the Roman Empire. Some saw it as divine intervention, while others speculated it was a masterful political maneuver, designed to secure the support of the growing Christian community

Regardless of its origins, the vision had far-reaching consequences. In 313 AD, Constantine and Licinius issued the Edict of Milan, granting Christians freedom of worship and restoring confiscated church property. This marked the beginning of Christianity’s rise to prominence within the empire.

By the time of his death in 337 AD, Christianity was no longer a fringe faith but the dominant religion of Rome. The cross he saw in the sky had become the emblem of an empire, and later, of Western civilization itself.

Would Rome have turned Christian without Constantine’s vision? Perhaps. But on that fateful evening in 312 AD, one man saw a symbol of hope, followed its message, and in doing so, reshaped the world.

Leave a comment