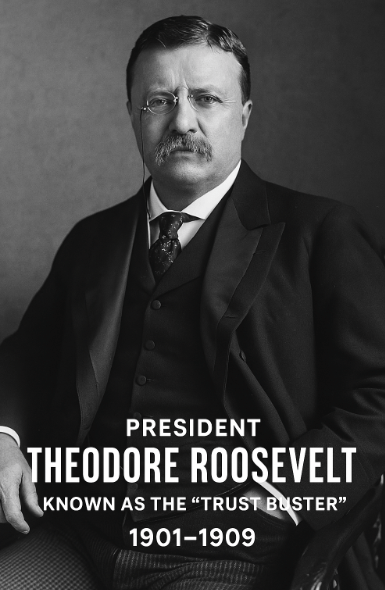

When Theodore Roosevelt became president in 1901, he brought with him a unique mix of cowboy swagger, progressive ideals, and an unshakable belief that government should serve the people—not the powerful. At a time when monopolies ruled much of the American economy, Roosevelt took the fight directly to the captains of industry. He wasn’t out to destroy business, but he wasn’t afraid to rein it in, either. This is the story of how a Rough Rider became the country’s first great Trust Buster.

The Gilded Age Giants

By the turn of the 20th century, America was booming—but so were its monopolies.

The Gilded Age had birthed towering industrial empires run by men like John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, and J.P. Morgan. These tycoons, often called “robber barons,” controlled everything from oil and steel to railroads and banking. Their corporations were organized into trusts—massive combinations of businesses that dominated entire industries, crushed competition, and set prices at will.

The government, for the most part, looked the other way. The Sherman Antitrust Act, passed in 1890 to prevent monopolies, was rarely enforced. Political leaders often owed their elections to the donations and influence of these business titans. The average American felt powerless.

That’s where Teddy Roosevelt saw his opening.

Roosevelt’s Philosophy: Regulation, Not Revolution

Roosevelt wasn’t a radical. He admired business innovation and believed that industrial growth had helped make America strong. But he also believed that unchecked corporate power was dangerous.

Rather than dismantle every big business, Roosevelt distinguished between “good trusts” and “bad trusts.” Good trusts operated fairly, treated workers decently, and didn’t abuse consumers. Bad trusts, on the other hand, used their size to crush competition, manipulate the market, and exploit their workers.

Roosevelt’s goal wasn’t to punish success—it was to ensure fairness, or what he called a “Square Deal” for everyone: capitalists, workers, and consumers alike. It was this vision that propelled him to take on some of the most powerful men in America.

Northern Securities: The First Big Fight

Roosevelt’s first major battle came in 1902 against the Northern Securities Company, a powerful railroad trust formed by J.P. Morgan, James J. Hill, and E.H. Harriman. The company had merged several competing rail lines in the Northwest, essentially creating a transportation monopoly that threatened to control the entire region’s economy.

Roosevelt shocked the business world when he ordered the Justice Department to sue the company under the Sherman Antitrust Act—a bold move that hadn’t been seriously attempted by a president before.

Morgan, one of the richest men in the world, confidently met with Roosevelt and offered to “fix things” privately. Roosevelt flatly refused, stating the issue had to be resolved in court, not behind closed doors. This marked a turning point in American politics—the president was no longer beholden to the business elite.

In 1904, the Supreme Court sided with Roosevelt and ordered the company to be dissolved. It was the first major antitrust victory in U.S. history and sent a clear message: the law applies to everyone—even Wall Street titans.

Bustin’ More Than Just One Trust

Roosevelt wasn’t done. Over the next several years, he launched 44 antitrust lawsuits, targeting monopolies in oil, beef, tobacco, and more.

One of his biggest targets was the Beef Trust, a cartel of meatpacking companies that fixed prices and shortchanged ranchers and consumers. Another was Standard Oil, the most powerful monopoly in the world, which was eventually broken up under Roosevelt’s successor, William Howard Taft, using the momentum Roosevelt had built.

These suits weren’t just legal battles—they were symbolic victories. Roosevelt showed Americans that no company was too big to challenge, and that government could be a check on corporate excess.

Yet, Roosevelt always made it clear he wasn’t anti-business. He often praised companies that played fair and even partnered with some industrial leaders to improve working conditions and safety standards. His legacy wasn’t about destroying capitalism—it was about balancing it.

The Man Who Faced J.P. Morgan

The clash between Roosevelt and J.P. Morgan has become legendary. When Morgan heard the government was suing Northern Securities, he was stunned. “If we have done anything wrong,” Morgan said, “send your man to see my man, and they can fix it up.”

But Roosevelt wasn’t interested in quiet deals. His reply was blunt: “That can’t be done.”

Roosevelt’s refusal to play by the old rules changed how business was done in Washington. He proved that no matter how rich or influential someone was, they couldn’t dictate policy from behind a velvet curtain.

This moment came to symbolize a new era of government accountability and executive power.

Legacy of the Trust Buster

By the time Roosevelt left office in 1909, he had forever changed the presidency. He expanded its role into that of a moral and economic leader, and he established the federal government as a referee in the battle between capital and labor.

His actions paved the way for future regulatory reforms, from food safety laws to the eventual breakup of monopolies like Standard Oil and American Tobacco. Roosevelt’s influence was so profound that both his allies and opponents recognized that government would never again be silent in the face of corporate power.

Final Thoughts: A Rough Rider for the People

Theodore Roosevelt didn’t just fight bears in the wilderness—he took on giants in the boardroom. With his bold, hands-on leadership style and unshakable sense of justice, he redefined what it meant to be president in a rapidly industrializing world.

Roosevelt didn’t believe in burning the system down. He believed in fixing it from within—with energy, courage, and a firm grip on the reins of government.

In an age when the rich and powerful called the shots, Teddy Roosevelt stood tall and reminded the nation: Even the biggest trusts are no match for the public good.

Leave a comment