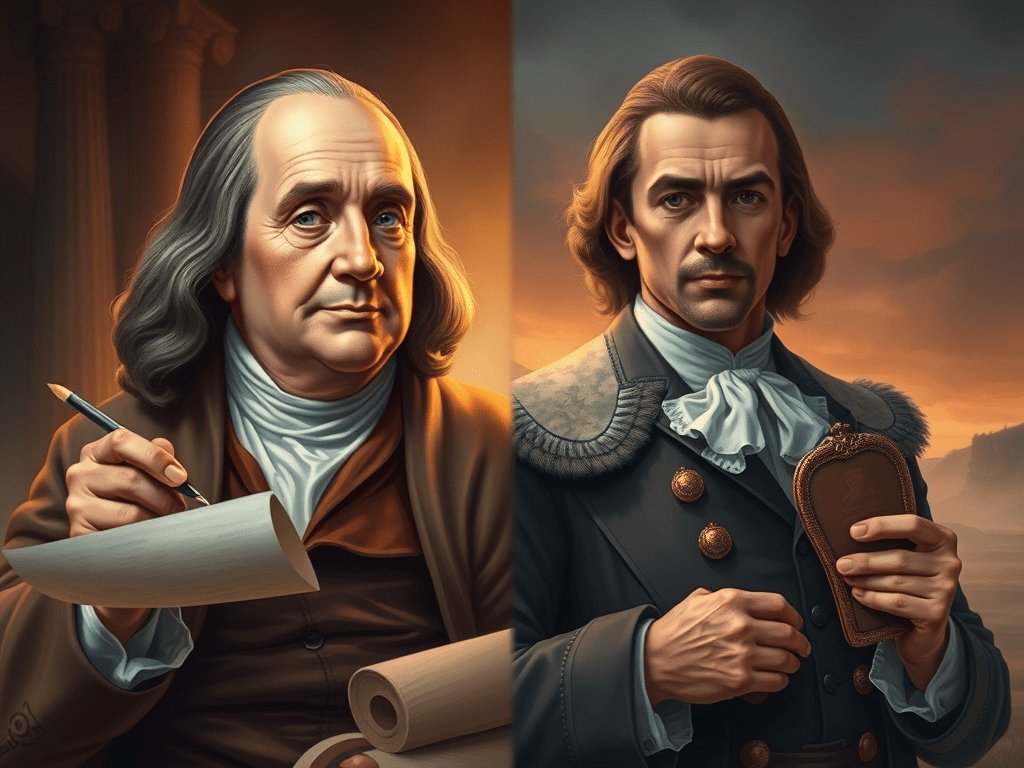

A Father and Son in Two Americas

In the tapestry of America’s founding, few figures loom as large as Benjamin Franklin—printer, inventor, diplomat, and Founding Father. Yet behind the wit, wisdom, and fame was a tragic, deeply personal conflict with his only acknowledged son, William Franklin. Their relationship—once close and affectionate—was torn apart by the ideological earthquake of the American Revolution. Benjamin embraced revolution; William clung to loyalty. In the end, the rupture between father and son mirrored the painful divisions of a nation.

The Early Years: Apprenticeship and Affection

William Franklin was born out of wedlock around 1730, likely in Philadelphia. The identity of his mother remains uncertain, though historians speculate she may have been a woman named Deborah Read, whom Franklin would later marry—or another woman entirely. Regardless, Franklin acknowledged William and raised him in his household. The two were close. Benjamin mentored William in science, politics, and ambition.

As a young man, William traveled with his father to London in 1757 when Franklin was lobbying on behalf of the Pennsylvania Assembly. There, William charmed British society. He studied law at the Inns of Court and cultivated a circle of elite acquaintances, including members of the British government.

The elder Franklin was grooming his son for greatness, and William showed promise. “He is as much my son in mind as in body,” Franklin once boasted to a friend.

Loyal to the Crown: William Becomes a Royal Governor

In 1762, with his father’s help and British connections, William was appointed Royal Governor of New Jersey by King George III. It was a prestigious post and a symbol of the Franklin family’s transatlantic rise. But the seeds of division were already sown.

Benjamin Franklin, though still loyal to the crown at the time, was growing disillusioned with British policies—especially their treatment of the American colonies. William, on the other hand, remained loyal to the monarchy, seeing British authority as legitimate and beneficial. He immersed himself in his duties as governor, often clashing with New Jersey’s colonial assembly, which mirrored the broader colonial resentment toward royal control.

Rising Tensions: A House Divided

The 1760s saw Franklin’s politics evolve. After the imposition of the Stamp Act in 1765, Benjamin emerged as a key figure in colonial resistance. His testimony before Parliament helped secure the act’s repeal, but tensions persisted. The Boston Massacre (1770) and the Tea Act (1773) fueled revolutionary fervor. Franklin, serving as colonial agent in London, was caught between two worlds.

In 1774, Franklin suffered a personal humiliation: he was publicly scolded by the British Privy Council in what became known as the “Cockpit” episode for leaking letters critical of colonial leadership. The incident was a turning point. Franklin returned to America in 1775, disillusioned and resolved to support the Patriot cause.

Meanwhile, William remained a committed Loyalist. Even as tensions exploded into war in April 1775 at Lexington and Concord, William stood by the crown, writing that rebellion was “a most unnatural crime.”

The lines were drawn. Father and son now stood on opposite sides of a revolution.

Betrayal and Imprisonment

In June 1776, the Continental Congress declared independence. Just days later, William was arrested by the New Jersey Provincial Congress for his refusal to recognize their authority. Held under house arrest, he was accused of conspiring with the British. Though he denied treason, intercepted letters showed he had corresponded with General Thomas Gage and supported British efforts to quell the rebellion.

The arrest devastated him—and deeply angered Benjamin Franklin. Though they exchanged a few letters early in the war, Benjamin eventually stopped writing. He saw William’s loyalty to the crown as betrayal—not just to his country, but to him personally.

William spent nearly two years in harsh conditions in Patriot prisons. In 1778, George Washington agreed to a prisoner exchange with British forces, and William was finally freed. He sailed to New York, then under British control, where he rejoined the Loyalist government and helped form the Board of Associated Loyalists, a group committed to suppressing the rebellion.

To the Patriots, he was a traitor. To Benjamin Franklin, he was worse: a lost son.

The Final Meeting: A Cold Reunion

After the war ended in 1783, William Franklin sailed to England in exile, one of many Loyalists who lost everything in America. He had been stripped of his governorship, his lands confiscated, and his name vilified. Yet he maintained his loyalty to the British cause to the end.

That same year, Benjamin Franklin, now a revered elder statesman, was serving as U.S. Minister to France. Peace negotiations brought him to England—and there, he saw William one last time.

The meeting was brief and strained. William expressed hope of reconciliation. Benjamin, aged and worn by war and politics, was distant. He wrote later that he tried to conceal “the anguish of my heart” during the meeting. They spoke of legal matters and pensions—but not of family, not of love.

Franklin did not forgive his son. In his final will, he left William almost nothing, writing:

> “The part he acted against me in the late war… has estranged him from my affections, and I hereby expressly exclude him from any share of my estate.”

Legacy: Two Franklins, Two Fates

Benjamin Franklin died in 1790 at the age of 84. Mourned by thousands, he was hailed as a Founding Father, diplomat, and philosopher. His legacy helped shape the new republic.

William Franklin died in obscurity in England in 1813, still a Loyalist, still estranged from the country he once governed. He never returned to America.

The tragedy of their relationship endures as a poignant reminder of how the Revolution fractured not just a nation, but families. Father and son, once close, became avatars of opposing visions. One believed in rebellion, liberty, and a new American identity. The other clung to the old world, to duty, and to a monarchy he believed just.

Their story is not just about politics—it’s about the painful cost of conviction, and the human heart torn by history.

Conclusion: The Revolution Within

In the great chronicles of the American Revolution, the story of Benjamin and William Franklin reveals a quieter, more personal kind of war—a revolution within a family. Their journey from affection to estrangement, from allies to adversaries, stands as one of the most compelling family dramas in early American history.

Benjamin Franklin once said, “There never was a good war or a bad peace.” Perhaps he spoke, in part, from the sorrow of losing his son—not to death, but to ideology. In that, he was like many Americans of his time, who found that liberty often demanded not just blood, but heartbreak.

—

Sources:

Isaacson, Walter. Benjamin Franklin: An American Life. Simon & Schuster, 2003.

Brands, H.W. The First American: The Life and Times of Benjamin Franklin. Anchor Books, 2002.

Franklin, Benjamin. Autobiography and Other Writings. Penguin Classics, 2003.

Fleming, Thomas. The Man Who Dared the Lightning: A New Look at Benjamin Franklin. William Morrow, 1971.

Morgan, Edmund S. Benjamin Franklin. Yale University Press, 2002.

“William Franklin.” Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/William-Franklin

Leave a comment