Prelude to a President’s Final Day

By the spring of 1945, Franklin Delano Roosevelt was more than just a president—he was the embodiment of American resilience. Since taking office during the bleakest days of the Great Depression in 1933, FDR had led the country through economic despair, crafted sweeping social reforms, and now stood as the principal architect of the Allied effort in World War II. He had been elected to an unprecedented fourth term in 1944, but the toll of twelve years in office and the burden of war had left visible marks.

Roosevelt’s health had been in steady decline for years. He suffered from hypertension, congestive heart failure, and had been diagnosed with arteriosclerosis. Despite these serious ailments, Roosevelt and his inner circle downplayed his condition. His doctors, particularly Admiral Ross McIntire, maintained an optimistic public front. Still, by early 1945, the president’s gaunt features, flagging energy, and slow gait made his decline impossible to ignore.

The Yalta Conference in February 1945 revealed just how frail Roosevelt had become. Photographs show him slouched and pale next to Churchill and Stalin. His face had lost its color, and his trademark grin appeared only in flickers. Despite this, FDR remained committed to forging the post-war peace. He envisioned the United Nations as a global institution that could prevent future world wars, and he poured himself into its creation, believing it would be his lasting legacy.

His doctors, finally conceding his fragile state, recommended rest. Roosevelt agreed to a stay at his cherished retreat in Warm Springs, Georgia—a place where, years earlier, he had sought therapy for the paralysis caused by polio. To him, Warm Springs was not just therapeutic—it was home.

Morning at Warm Springs

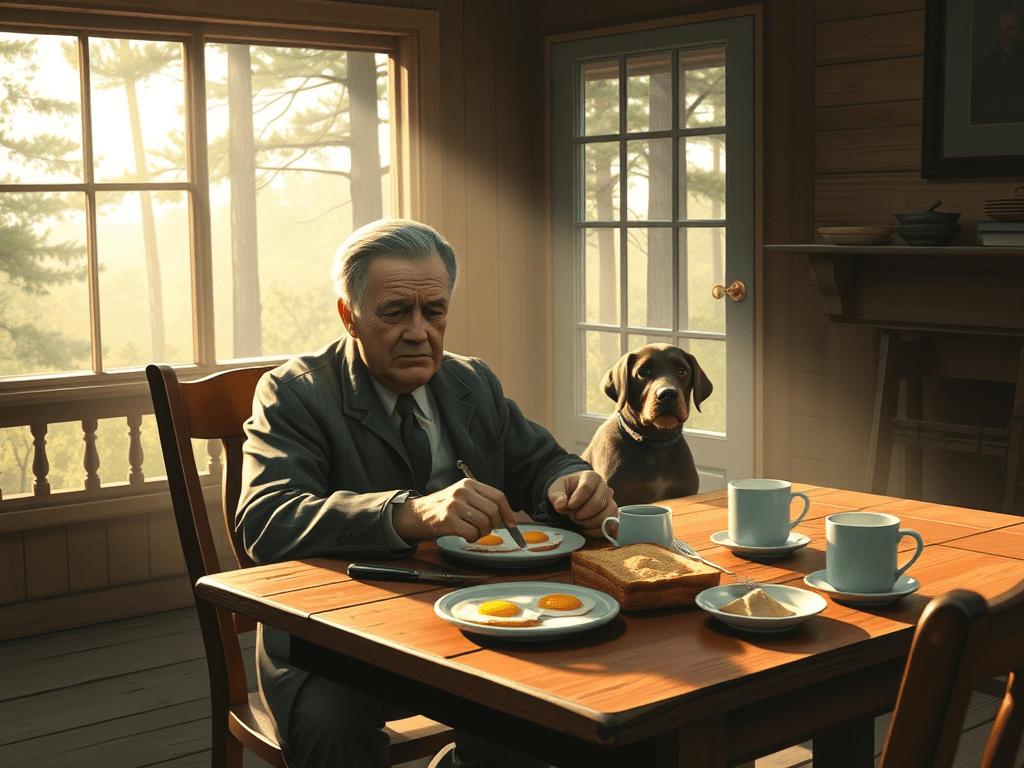

On the morning of April 12, 1945, Franklin Roosevelt awoke in his modest cottage at Warm Springs—known affectionately as the “Little White House.” The sun filtered through the pine trees as he began what was expected to be a quiet day. Staff members brought him a simple breakfast of scrambled eggs, toast, and coffee. His beloved Scottish Terrier, Fala, was nearby, as always.

He was not alone. Among the guests at Warm Springs that week were several aides and confidantes, including Lucy Mercer Rutherfurd—a woman who had once been the source of a great scandal. Lucy and FDR had rekindled their friendship (and likely their romantic connection) in later years with Eleanor Roosevelt’s quiet tolerance. Also present were Daisy Suckley, his cousin and confidante; Grace Tully, his loyal secretary; and Dr. Howard Bruenn, his physician.

Despite his ill health, Roosevelt remained engaged with affairs of state. On his desk was a draft of a speech he intended to deliver on Jefferson Day—April 13—a celebration of Thomas Jefferson’s birthday. The speech was to be broadcast over the radio, continuing FDR’s tradition of using powerful oratory to reach the American public directly.

Roosevelt was seated in a high-backed chair by the fireplace, posing for a watercolor portrait by Russian-born artist Elizabeth Shoumatoff. He was unusually animated, discussing the portrait and talking about his plans for post-war diplomacy. But then, just after 1:00 p.m., his mood suddenly shifted. According to Shoumatoff and others in the room, he brought his hand to his head and said, “I have a terrific pain in the back of my head.”

Moments later, he slumped forward. Dr. Bruenn was called immediately. After a quick examination, the diagnosis was grim and immediate: a massive cerebral hemorrhage. There was no hope of recovery. Roosevelt never regained consciousness.

At 3:35 p.m., Franklin Delano Roosevelt was pronounced dead.

“The President is Dead” — News Breaks

In Washington, the gears of government continued to turn, though many were unaware that their leader had fallen. Vice President Harry S. Truman, who had been largely kept out of high-level wartime decisions, was presiding over a Senate committee meeting when he received an urgent message to come to the White House.

Truman had been vice president for only 82 days. During that short period, he had been kept in the dark about some of the most significant matters of state—including the top-secret Manhattan Project. The Roosevelt administration had long operated with a tight inner circle, and Truman was not part of it.

When Truman arrived at the White House, he was met by Eleanor Roosevelt. Her face was drawn, her eyes tired. She looked at him gravely and spoke words that would echo through history: “Harry, the president is dead.”

The vice president, visibly shaken, asked what he could do for her.

“No,” she replied gently. “Is there anything we can do for you? For you are the one in trouble now.”

At 7:09 p.m., Truman was sworn in as the 33rd president of the United States by Chief Justice Harlan F. Stone in the Cabinet Room. The ceremony was brief, somber, and witnessed by a handful of officials and family members. The weight of the presidency settled heavily on Truman’s shoulders. He had gone from an unassuming senator from Missouri to commander-in-chief in the final months of the most destructive war in history.

The People Mourn

News of Roosevelt’s death spread across the nation and the world with stunning speed. Radios interrupted their regular programming. Newspaper boys ran through the streets, shouting headlines. In factories, work stopped. In schools, teachers broke into tears.

In a nation already steeped in grief and wartime sacrifice, Roosevelt’s death felt deeply personal. He had been the only president a generation of Americans had ever known. From the depths of the Great Depression to the zenith of global conflict, FDR had been a steady voice—hopeful, defiant, and eloquent.

In Harlem, black Americans wept openly in the streets. Though Roosevelt had not aggressively advanced civil rights, his New Deal programs had provided relief to many, and his willingness to appoint African Americans to government roles had earned him lasting admiration.

In rural towns, farmers pulled over their wagons. Shopkeepers closed early. Millions of Americans gathered around radios, many not believing what they were hearing. In New York City, tens of thousands converged on Times Square. The city fell eerily silent.

Abroad, the reactions were no less emotional. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill addressed Parliament in mourning and canceled the evening’s scheduled military operations as a gesture of respect. In the Soviet Union, Josef Stalin—never known for warmth—sent a rare telegram of condolence and ordered a minute of silence across the Red Army.

The Artist’s Unfinished Portrait

Back at Warm Springs, the artist Elizabeth Shoumatoff sat stunned. Her portrait of Roosevelt—still on the easel—was frozen in time, just as he had been when the stroke hit. She chose never to complete the original, instead finishing a second version from memory later.

The two versions—one unfinished, one complete—remain a potent symbol. The first captures the president mid-sentence, mid-breath, mid-life. It has become a visual representation of that singular, sudden moment when history shifted course.

Also on the desk was the draft of Roosevelt’s last speech. Its final written words carried eerie resonance:

“The only thing we have to fear is fear itself… The work, my friends, is peace: more than an end of this war—an end to the beginning of all wars.”

Even in his final hours, Roosevelt’s focus was on what would come after the war. He did not live to see the surrender of Germany or Japan. But he had laid the foundation for the United Nations, which would be formally established just months later.

Truman Steps In

The transition from Roosevelt to Truman was abrupt and momentous. Though Harry Truman was a seasoned politician, he was not prepared for the scope of responsibility now thrust upon him. He had never been fully briefed on major wartime strategy. The day after Roosevelt’s death, he was informed of the existence of the atomic bomb by Secretary of War Henry Stimson.

Over the next four months, Truman would oversee the conclusion of World War II. He would attend the Potsdam Conference, receive news of Germany’s surrender, authorize the use of atomic weapons on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and confront the immense challenge of postwar reconstruction.

He approached the task humbly. “Boys, if you ever pray, pray for me now,” he reportedly told reporters after being sworn in.

Though he lacked Roosevelt’s charisma, Truman had his own virtues: decisiveness, moral clarity, and resilience. But the shift in leadership also marked a turning point in American politics. Roosevelt’s death brought to an end the era of sweeping New Deal liberalism and introduced a more pragmatic, postwar governance.

Legacy and Reflection

Franklin Roosevelt was more than a political leader—he was a figure of mythic proportions. His leadership reshaped the United States socially, economically, and internationally. He expanded the power of the federal government, brought millions out of poverty, and steered the nation through its most perilous trials.

Yet, his legacy is also one of complexity. He failed to challenge segregation in any meaningful way, allowed the internment of Japanese Americans, and hesitated to intervene in the Holocaust. Still, his transformative vision and force of personality made him one of the most consequential figures of the 20th century.

In death, Roosevelt became a symbol of continuity broken—a reassurance lost. But he also became a symbol of what American leadership could be: eloquent, bold, and anchored in the belief that government could be a force for good.

Sources

- Jean Edward Smith, FDR – A comprehensive and well-researched biography.

- Doris Kearns Goodwin, No Ordinary Time – Explores Roosevelt’s leadership during WWII and his domestic policies.

- A.J. Baime, The Accidental President: Harry S. Truman and the Four Months That Changed the World – A vivid account of Truman’s sudden rise.

- The Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum – Primary source materials and speech drafts.

- Warm Springs Historic Site and Little White House Museum – Archival records and the story of the unfinished portrait.

- Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) – American Experience: FDR documentary series.

- The New York Times, April 13, 1945 – Eyewitness accounts and national reaction to Roosevelt’s death.

- National Archives and Records Administration – Truman’s swearing-in and early presidential decisions.

Leave a comment