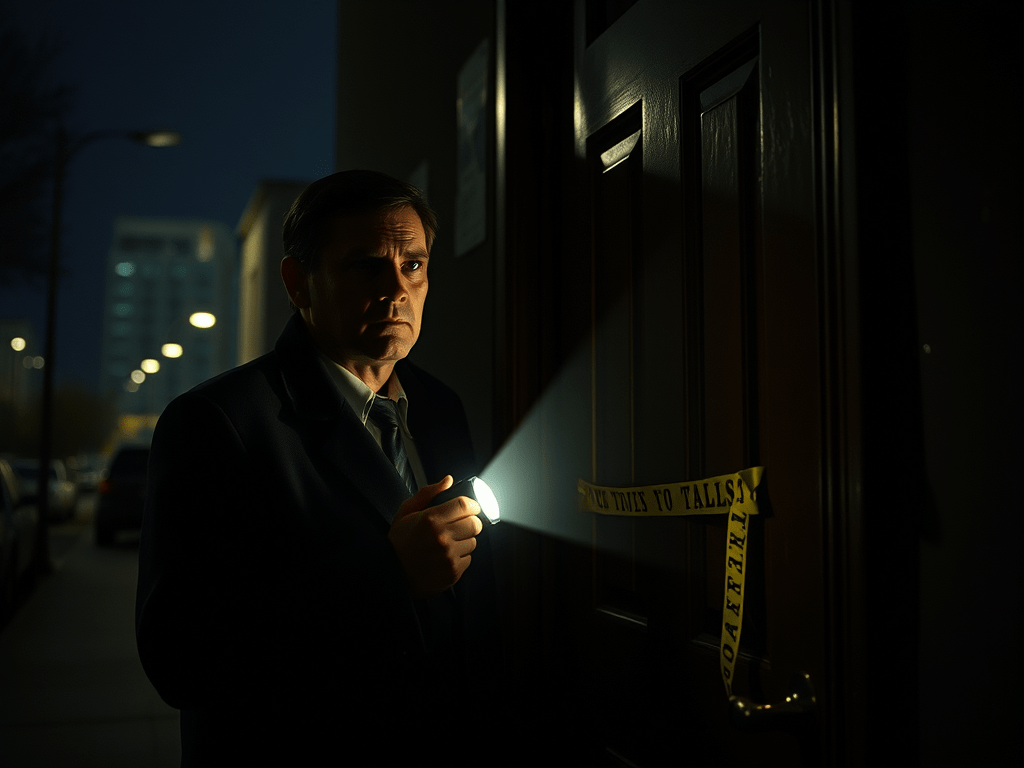

Prologue: A Flashlight in the Dark

It began like an ordinary night for Frank Wills, a security guard working the graveyard shift at the Watergate office complex in Washington, D.C. But shortly after midnight on June 17, 1972, he noticed something odd: duct tape on a door latch, keeping it from locking. Wills removed the tape, only to discover later that someone had re-applied it. Suspicious, he called the police.

What the officers found inside the Democratic National Committee (DNC) headquarters would seem surreal in retrospect—five men wearing business suits and rubber gloves, carrying wiretapping devices, cameras, and large sums of cash. They were caught red-handed in the act of bugging phones and photographing documents.

Though at first glance it looked like a strange burglary, the incident would become the opening scene in a drama that would shake the American political system to its foundation.

The Break-In Nobody Understood—At First

The arrested men were not ordinary criminals. James McCord was a former CIA officer and head of security for the Committee to Re-elect the President (CREEP). The others—Bernard Barker, Virgilio González, Eugenio Martínez, and Frank Sturgis—had ties to the CIA and anti-Castro operations.

Why would operatives with such backgrounds break into a political headquarters? At first, few in the press or public paid much attention. Most news outlets treated it as a one-off story. But two young reporters at The Washington Post, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, sensed something deeper. Under the guidance of editor Ben Bradlee and publisher Katharine Graham, they began following a trail of names, bank transactions, and lies.

Their investigation quickly pointed to something explosive: this was no isolated crime. The break-in was tied to a web of political espionage and dirty tricks orchestrated by the highest echelons of power.

CREEP, Dirty Tricks

President Richard Nixon was running for re-election in 1972 and wanted an overwhelming victory. Though he was already favored to win, paranoia and a hunger for absolute control led his campaign to approve aggressive measures to sabotage opponents.

The Committee to Re-elect the President, or CREEP, wasn’t just organizing rallies and buying ads. It financed clandestine operations to spy on Democratic candidates and disrupt their campaigns. Under the leadership of former FBI agent G. Gordon Liddy and ex-CIA officer E. Howard Hunt, a secret team carried out surveillance, wiretaps, and smear campaigns.

Liddy’s proposals bordered on the absurd: bugging hotels, staging kidnappings, and sending prostitutes to Democratic events. While many ideas were dismissed as too risky, some—including the Watergate break-in—were approved. The goal was to gain an edge in the upcoming election at any cost.

Follow the Money

Woodward and Bernstein methodically traced financial connections between the burglars and the Nixon campaign. One breakthrough came when a $25,000 check from a Republican donor turned up in a burglar’s bank account.

More digging revealed a campaign slush fund used to finance not just the break-in but an entire program of political espionage. As they uncovered more, the reporters relied heavily on a mysterious source they dubbed “Deep Throat,” who met Woodward in underground parking garages and passed along cryptic tips.

“Follow the money,” he told them—and they did, all the way to the White House.

The Cover-Up Begins to Crack

The Nixon administration moved quickly to distance itself from the break-in. Publicly, they denied any involvement. Privately, they paid hush money to the burglars, instructed aides to obstruct the FBI investigation, and pushed the narrative that the break-in had been an independent operation by overzealous underlings.

Yet the cover-up began to falter in 1973. Under pressure from Judge John Sirica, James McCord broke his silence. In a letter to the court, he claimed that top officials were involved in perjury and obstruction of justice.

The Senate convened hearings in May 1973, chaired by Democrat Sam Ervin. Americans watched in disbelief as White House officials testified on live television. The hearings painted a picture of systemic abuse of power, with Nixon at the center.

Former White House counsel John Dean delivered a particularly damning testimony, describing a meeting where he warned Nixon of “a cancer on the presidency.” Dean detailed the elaborate efforts to cover up the burglary and protect those involved.

The Smoking Gun: Tapes in the Oval Office

Then came the revelation that would turn suspicion into certainty. In July 1973, White House aide Alexander Butterfield disclosed that Nixon had a voice-activated taping system recording every conversation in the Oval Office.

The tapes became the focal point of the investigation. Nixon refused to hand them over, citing executive privilege and national security. A fierce legal battle ensued, culminating in the Supreme Court case United States v. Nixon (1974).

In a unanimous decision, the Court ruled that Nixon had to surrender the tapes. When the recordings were finally released, they confirmed what many feared: Nixon had approved the cover-up within days of the break-in. One tape from June 23, 1972—known as the “smoking gun”—recorded Nixon discussing how to use the CIA to shut down the FBI investigation.

Resignation and Aftermath

By August 1974, Nixon’s support had collapsed. Facing imminent impeachment, he chose to resign. On August 8, he addressed the nation in a solemn televised speech, announcing that he would step down to preserve the integrity of the presidency.

The next morning, Nixon boarded Marine One on the South Lawn of the White House, giving his signature double-V peace sign before disappearing into history.

Vice President Gerald Ford was sworn in and, weeks later, issued a controversial pardon granting Nixon full immunity from prosecution. Ford argued it was necessary for national healing, but many Americans saw it as a miscarriage of justice.

Legacy: A Broken Trust

Watergate left a deep scar on the American political landscape. It led to a wave of reforms designed to increase transparency and limit executive overreach.

Congress amended the Federal Election Campaign Act, established new ethics rules for public officials, and passed the Ethics in Government Act, which created the role of the independent counsel. The Freedom of Information Act was strengthened to allow greater access to government records.

Perhaps most importantly, the scandal forever changed the relationship between the press and the presidency. Investigative journalism was revitalized, and the American people became more skeptical of political power.

Who Paid the Price?

Dozens of officials faced legal consequences. Among them:

- H. R. Haldeman, Nixon’s chief of staff, served 18 months.

- John Ehrlichman, domestic affairs adviser, served 18 months.

- John Mitchell, former attorney general, served 19 months.

- G. Gordon Liddy, convicted of conspiracy and burglary, served over four years.

- E. Howard Hunt, the break-in mastermind, served 33 months.

In total, 69 people were indicted and 48 were convicted. Nixon avoided prosecution, but his legacy was irreparably damaged.

He spent his later years writing books and giving interviews, trying to rehabilitate his image. He died in 1994, still a deeply polarizing figure.

Conclusion: The Scandal That Changed Everything

Watergate was not just a political scandal; it was a constitutional crisis. It revealed the fragility of American democracy and the dangers of unchecked power.

It also showcased the resilience of American institutions: the judiciary, the press, and the courage of individuals who refused to be silenced.

In the end, Watergate proved that no one—not even the president—is above the law.

Sources

- Woodward, Bob and Carl Bernstein. All the President’s Men. Simon & Schuster, 1974.

- Kutler, Stanley I. The Wars of Watergate: The Last Crisis of Richard Nixon. Knopf, 1990.

- Emery, Fred. Watergate: The Corruption of American Politics and the Fall of Richard Nixon. Times Books, 1994.

- “Watergate Scandal.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, https://www.history.com/topics/1970s/watergate

- United States v. Nixon, 418 U.S. 683 (1974)

- National Archives: Watergate Special Prosecution Force Records, https://www.archives.gov/research/investigations/watergate

Leave a comment