A Gamble Like No Other

The summer of 1944 was do-or-die for the Allied war effort. Hitler’s Third Reich still controlled most of Western Europe, and despite major victories in Italy and the Eastern Front, the Allies had yet to open a western land corridor into Nazi-occupied territory. The plan to invade Normandy, codenamed Operation Overlord, had been years in the making—a combined effort of intelligence operatives, military strategists, engineers, and commanders from more than a dozen nations.

The scale was unprecedented: over 2 million Allied troops were based in Britain, preparing for the assault. The key challenge? Deceiving the Germans about when and where the strike would occur. Using an elaborate ruse called Operation Fortitude, the Allies tricked German intelligence into believing the main invasion would land at Pas-de-Calais, not Normandy. Inflatable tanks, fake radio chatter, and a dummy army under General George Patton reinforced the illusion.

Yet no amount of preparation could guarantee success. Eisenhower knew that if the invasion failed, it might set the war back by years and cost hundreds of thousands more lives. With a storm system hammering the English Channel, the initial launch date of June 5 was postponed. On the night of June 5, meteorologists predicted a brief break in the weather. Eisenhower took a deep breath and gave the order: “OK. Let’s go.”

Before the Dawn: Operation Neptune

The naval component of the invasion—Operation Neptune—was a logistical marvel. More than 5,000 ships, including battleships, cruisers, destroyers, troop transports, and landing craft, set out across the Channel. Naval bombardments began early on the morning of June 6, targeting German fortifications along the coast.

Meanwhile, 11,000 aircraft filled the skies. Bombers softened up targets inland, while gliders and transport planes carried 23,000 paratroopers into the dark Norman countryside.

The beaches were divided into five sectors: Utah and Omaha (assigned to American forces), Gold and Sword (British), and Juno (Canadian). Each presented unique challenges, from geography and tide patterns to the strength and placement of German fortifications.

Soldiers were seasick, nervous, and soaked from the choppy crossing. For many, the reality of war didn’t hit until the landing craft ramp dropped and they were met with bullets.

Omaha Beach: Into the Teeth of Hell

Of all the landing zones, Omaha Beach became synonymous with bloodshed and heroism. The Americans faced the 352nd German Infantry Division, a well-trained, battle-hardened unit that had unexpectedly reinforced the area just weeks before.

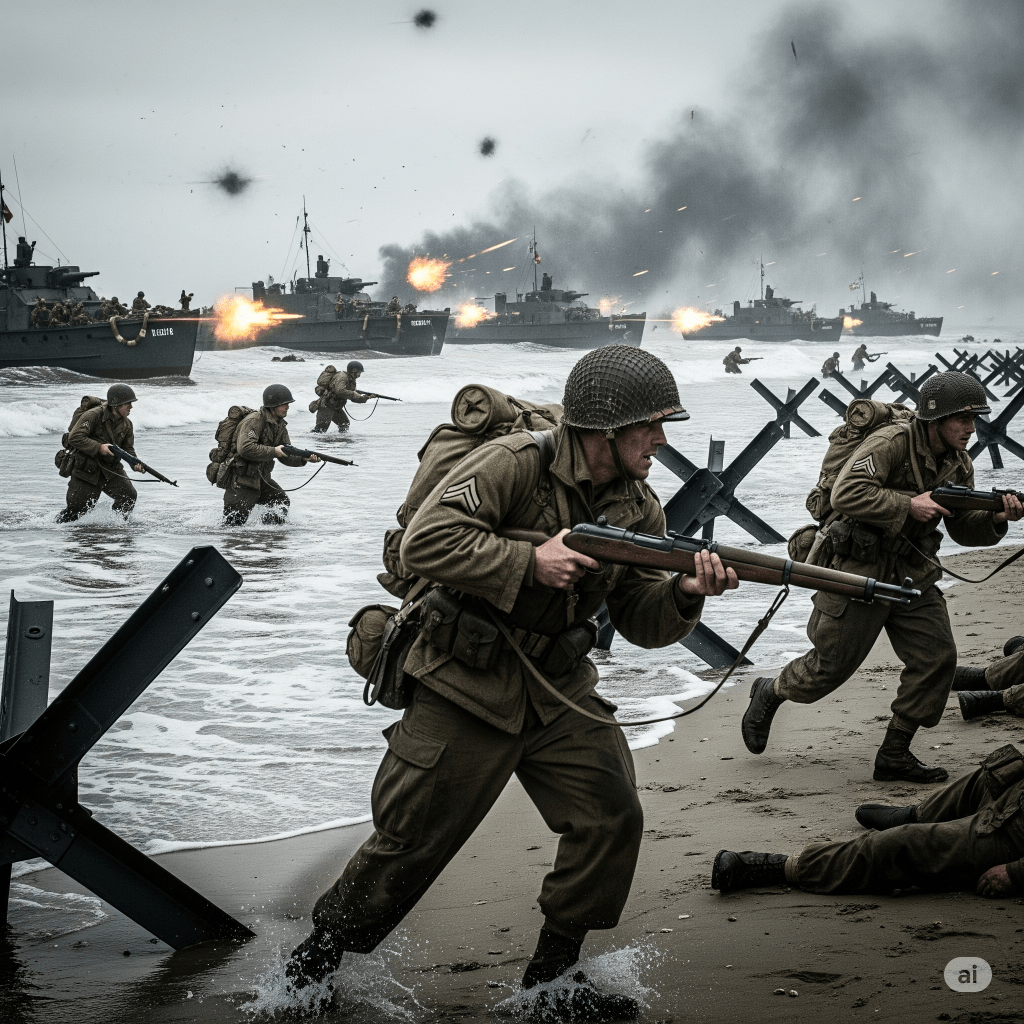

When the first waves of the 1st and 29th U.S. Infantry Divisions landed around 6:30 a.m., the scene was apocalyptic. Many landing craft missed their targets due to strong currents. Troops were unloaded in deep water, forcing them to wade ashore under withering fire from German MG42 machine guns, mortars, and artillery perched atop the bluffs.

The terrain offered no cover—just wet sand and steel obstacles. Entire units were cut down before reaching dry land. Tanks, meant to support the infantry, often sank due to rough seas.

Captain Joe Dawson, one of the first officers to breach the German defenses, recalled the horror: “The bodies were everywhere. It was like a nightmare you couldn’t wake up from.”

And yet, against all odds, small groups of soldiers began climbing the bluffs, tossing grenades into bunkers and knocking out machine-gun nests. By afternoon, they had broken through and begun moving inland. But the cost was staggering: 2,400 casualties, the highest of any beach.

Utah, Gold, Juno, Sword: The Other Fronts of Fury

At Utah Beach, the landings were more successful, partly due to the effectiveness of U.S. airborne divisions dropped behind enemy lines. The 4th Infantry Division, led by Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt Jr.—who insisted on landing with the first wave despite heart problems and arthritis—found themselves over a mile off course. Roosevelt reportedly looked around and said, “We’ll start the war from right here.” His calm leadership was instrumental in organizing the scattered troops. Resistance was lighter than expected, and by the end of the day, the Americans had pushed several miles inland.

At Gold Beach, British forces of the 50th Infantry Division encountered heavy resistance from fortified German positions in the town of Le Hamel. Despite this, they managed to capture the town of Bayeux by the following day—the first major city to be liberated in the invasion.

The Canadians at Juno Beach faced the second-heaviest resistance of the day. Delayed by obstacles and rough seas, they landed after the tide had come in, reducing the available beach space and making them easier targets. The 3rd Canadian Infantry Division was met by concrete bunkers and anti-tank guns but managed to push farther inland than any other force, linking up with the British and securing key roads.

At Sword Beach, British troops of the 3rd Infantry Division faced counterattacks from the 21st Panzer Division, one of the few organized German responses of the day. Though slowed by fierce fighting in Caen, the British held their ground, aided by French Resistance fighters who sabotaged German communications.

The Airborne Gamble

The airborne operations of the 82nd and 101st U.S. Airborne Divisions and the British 6th Airborne Division were vital to D-Day’s success—but they were also some of the riskiest components of the invasion.

Paratroopers dropped in the early hours of June 6 under cover of darkness. Poor weather, flak, and navigation errors caused massive dispersals. Some units landed in flooded marshes and drowned under heavy equipment. Others landed in enemy-occupied towns and were quickly captured or killed.

Despite this chaos, airborne troops accomplished key objectives. The British 6th Airborne secured the Pegasus Bridge, a vital link across the Orne River, preventing German armor from reaching Sword Beach. American paratroopers captured road junctions, secured causeways off Utah Beach, and disrupted German reinforcements.

Stories of courage emerged from every unit. At La Fière Bridge, a small group of paratroopers held off a German armored counterattack, ensuring that Utah Beach could be reinforced. These isolated pockets of resistance often fought alone for days until regular forces reached them.

The German Response: Confusion and Delays

The German high command was unprepared for the scale and location of the invasion. The Atlantic Wall, Hitler’s vaunted defensive line, was incomplete and inconsistently manned. Hitler and his inner circle were convinced that the main attack would still come at Pas-de-Calais—even as thousands of Allied troops stormed Normandy.

When the invasion began, many top German commanders were away from their posts, and Hitler refused to release the Panzer divisions without direct orders—orders he did not give until the afternoon of June 6. The delay cost the Germans dearly.

General Erwin Rommel, tasked with defending the coast, had returned to Germany to celebrate his wife’s birthday. He had argued that the Allies must be defeated on the beaches before they could gain a foothold. His warnings were ignored, and by the time he returned to Normandy, it was too late.

The Fight Inland: Hedgerows and Resistance

With the beaches secured, the next challenge was moving inland. Normandy’s landscape was a nightmare: bocage country—dense hedgerows, sunken roads, and small fields surrounded by thick vegetation. These natural barriers became deadly traps for advancing Allied troops.

German snipers, machine-gunners, and artillery used the hedgerows for ambushes. Movement was slow, often house-to-house and field-by-field. Tanks struggled to navigate the narrow roads and were picked off by German Panzerfausts and 88mm guns.

One of the fiercest battles took place in Carentan, where American paratroopers of the 101st Airborne fought a weeklong battle to link up the Utah and Omaha Beachheads. At Caen, British forces endured weeks of grueling combat, only taking the city in mid-July.

To break the stalemate, the Allies developed new tactics. Engineers welded steel “teeth” to tanks to plow through hedgerows. Air power was increasingly used to blast open German defenses. Progress was measured in yards, not miles.

Civilian Toll and French Resistance

Normandy’s civilians bore a heavy burden. Allied bombings, while necessary to weaken German defenses, devastated towns like Caen and Saint-Lô. Thousands of civilians were killed or left homeless. Despite the danger, many Normans aided the Allies, offering intelligence, sheltering soldiers, or joining the Forces Françaises de l’Intérieur (FFI)—the armed wing of the French Resistance.

The Resistance played a crucial role in the days after the landings. They sabotaged railway lines, cut telephone wires, and ambushed German patrols. One Resistance leader, Marie-Madeleine Fourcade, coordinated espionage networks that provided crucial maps and intelligence to Allied planners.

In return, the Nazis retaliated brutally. The massacre at Oradour-sur-Glane, where an SS division murdered 642 civilians in a single day, remains one of the most horrifying atrocities of the war.

Legacy of June 6, 1944

By June 30, the Allies had landed nearly 850,000 troops, 150,000 vehicles, and 570,000 tons of supplies in Normandy. Though the German army continued to resist fiercely, the writing was on the wall.

The liberation of Paris followed on August 25, 1944, and the Allies continued their push across France, Belgium, and into Germany. D-Day marked the turning point in the war in Europe.

The cost was immense: over 10,000 Allied casualties on D-Day alone. Thousands more would die in the coming weeks. But their sacrifice forged a path to freedom and demonstrated that courage, coordination, and conviction could overcome even the most entrenched evil.

Today, Normandy’s beaches are quiet, watched over by cemeteries, memorials, and grateful descendants of those who were freed.

Sources:

- Ambrose, Stephen E. D-Day: June 6, 1944: The Climactic Battle of World War II. Simon & Schuster, 1994.

- Atkinson, Rick. The Guns at Last Light: The War in Western Europe, 1944–1945. Henry Holt, 2013.

- Keegan, John. The Second World War. Penguin, 1990.

- U.S. Army Center of Military History: https://history.army.mil

- National D-Day Memorial: https://www.dday.org

- Imperial War Museums: https://www.iwm.org.uk

Leave a comment