The Meeting That Changed History

In 48 BCE, the world stood at a crossroads. Rome was in chaos, riven by civil war. Julius Caesar, fresh from defeating his rival Pompey the Great at the Battle of Pharsalus, pursued the fleeing general to Egypt. What he found instead was a tangled dynastic struggle between the young Ptolemaic rulers—Cleopatra VII and her brother-husband, Ptolemy XIII.

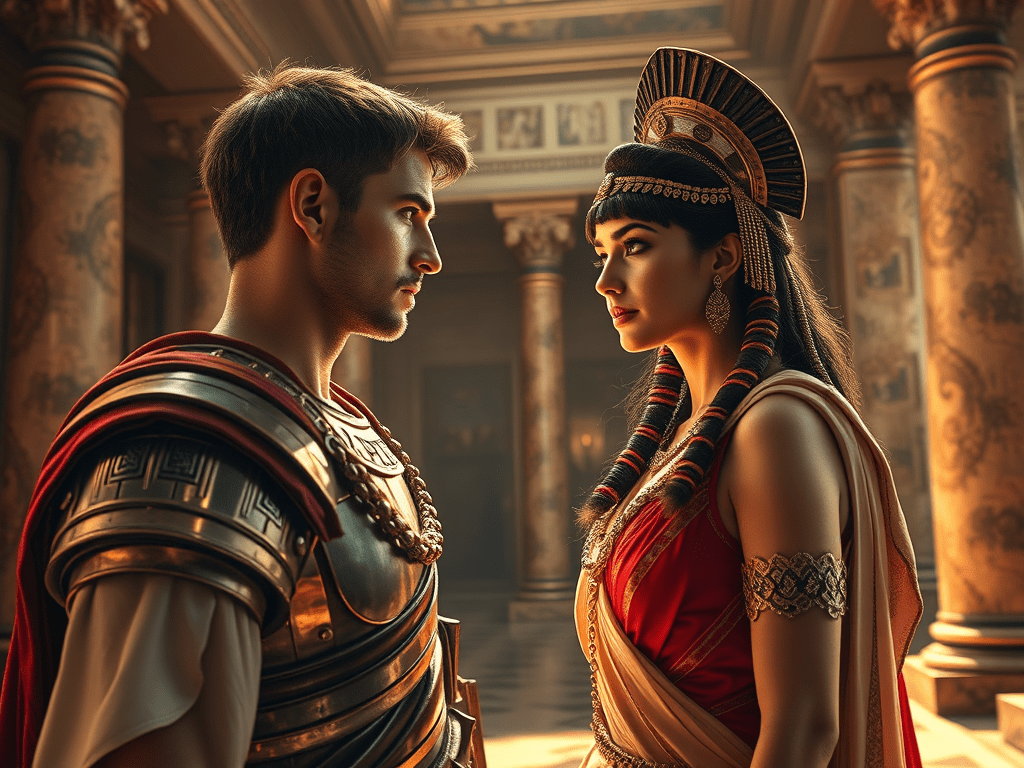

It was here, in the opulent halls of Alexandria’s royal palace, that one of history’s most legendary relationships began. Cleopatra, just 21 years old but already politically astute, famously had herself smuggled into Caesar’s presence—likely rolled in a rug or linen sack—to appeal for his support in her claim to the Egyptian throne.

Caesar, 52 at the time and a man of both ambition and appetite, was captivated.

Cleopatra: The Queen and the Strategist

Cleopatra was not the exotic seductress later dramatized in Roman propaganda and Elizabeth Taylor films. She was a multilingual scholar who spoke nine languages, including Egyptian—a rarity among her Greek-descended Ptolemaic dynasty. She was a shrewd politician who understood that aligning herself with Caesar could secure her throne—and Egypt’s independence from Rome’s tightening grip.

Caesar, for his part, saw strategic value in supporting Cleopatra. Egypt was wealthy, agriculturally rich, and geopolitically essential. By backing Cleopatra over her brother, he could ensure a grateful, loyal monarch in a key client kingdom.

The alliance was not just political—it turned romantic. Despite being married (as was Cleopatra), Caesar began a public affair with the Egyptian queen. She bore him a son in 47 BCE: Ptolemy XV Philopator Philometor Caesar, better known as Caesarion—”little Caesar.”

War, Flames, and an Egyptian Victory

Caesar’s involvement in Egypt drew him into Alexandria’s civil war. In the early months of 47 BCE, Roman troops loyal to Caesar clashed with those supporting Ptolemy XIII. The fighting engulfed parts of the city, and during the infamous Siege of Alexandria, much of the Great Library is believed to have been damaged or destroyed—a symbolic casualty of political ambition.

Cleopatra remained at Caesar’s side during the conflict. Eventually, Roman reinforcements under Mithridates of Pergamon arrived, turning the tide. Ptolemy XIII drowned in the Nile trying to flee. With her rivals defeated, Cleopatra was restored to the throne, this time ruling with another younger brother, Ptolemy XIV (whom she may have later poisoned to make way for Caesarion).

Rome Meets the Nile

After securing Cleopatra’s rule, Caesar lingered in Egypt for several months—far longer than Roman elites thought proper. The Roman Senate seethed with gossip: what was the dictator doing in Alexandria with a foreign queen? Rumors swirled that Caesar was enthralled, even bewitched. He was given the mocking title “King of Bithynia’s Queen”, referencing earlier rumors about his alleged homosexual affair with a foreign king.

In reality, Caesar was not bewitched—he was consolidating power. He returned to Rome in late 47 BCE, bringing Cleopatra and Caesarion with him for a state visit. Cleopatra stayed in a villa outside the city walls (foreign royalty could not reside in the city proper), while Caesar refused to recognize her son publicly, though many believed Caesarion to be his heir.

Cleopatra’s presence in Rome caused a scandal. Caesar, always defiant of tradition, placed a golden statue of her in the Temple of Venus Genetrix, aligning her with his supposed divine lineage from Venus. This move angered many traditionalists, especially as Caesar was already behaving like a monarch—taking lifelong consulship, receiving honors, and even having coins struck with his face.

The idea that Caesar might make Cleopatra queen of Rome—or declare Caesarion as his heir—deeply disturbed the Senate.

The Ides of March and Cleopatra’s Escape

On March 15, 44 BCE, Julius Caesar was assassinated by a group of senators led by Brutus and Cassius. They stabbed him 23 times on the Senate floor, believing they were saving the Republic from tyranny.

Cleopatra, still in Rome at the time, quickly realized her position was dangerous. With Caesar dead and her future uncertain, she fled back to Egypt with Caesarion. She needed to protect her dynasty—and distance herself from Roman infighting.

But the seeds of revolution had already been sown.

After Caesar: A Power Vacuum and a New Roman Flame

In the wake of Caesar’s death, a power struggle consumed Rome. Cleopatra initially supported Caesar’s assassins, perhaps hoping to remain neutral or back the winning side. But she soon aligned with Mark Antony, one of Caesar’s closest allies, who took control of the eastern Roman provinces.

Their infamous romance blossomed into a partnership that shook the foundations of Rome. Cleopatra bore Antony three children and declared Caesarion Caesar’s rightful heir—openly challenging Octavian (Caesar’s grandnephew and adopted son, later Augustus).

This led to the Final War of the Roman Republic, culminating in the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE. Octavian’s forces defeated Antony and Cleopatra’s fleet. A year later, with Octavian closing in on Alexandria, Antony and Cleopatra both committed suicide—he by falling on his sword, she allegedly by asp bite.

Caesarion’s Fate and the End of the Ptolemies

After Cleopatra’s death, Caesarion briefly ruled as Pharaoh. But Octavian, now sole master of Rome, saw the boy as a threat. Caesarion was captured and executed in 30 BCE, ending the Ptolemaic dynasty and cementing Egypt as a Roman province.

Though Caesar never formally acknowledged Caesarion, Cleopatra insisted he was his father—and Caesar’s political enemies seemed to believe it. Octavian, now Augustus, spread the message that only he was Caesar’s true heir, erasing Caesarion from history.

Long-Term Effects of the Caesar-Cleopatra Alliance

1. Egypt’s Loss of Independence

Cleopatra’s gamble to preserve Egypt’s autonomy by aligning with Caesar ultimately failed. After her death, Egypt became a Roman province, governed by a Roman prefect rather than a king or queen.

2. Shift Toward Roman Empire

Caesar’s relationship with Cleopatra—and his behavior in the wake of it—helped justify fears that he sought to be king. This paranoia directly led to his assassination, which in turn accelerated the fall of the Republic and the rise of the Empire.

3. Legacy of Caesarion

Though erased from Roman records, Caesarion remained a symbol of a lost lineage—a vision of what might have been if Caesar had lived. His death underscored Rome’s ruthless commitment to centralizing power.

4. A New Model of Monarchy

Cleopatra’s public role as co-ruler and consort changed perceptions of female power in both the East and West. Her image—later romanticized and vilified—endured through millennia as a symbol of female leadership, allure, and ambition.

5. Enduring Romance and Myth

The relationship between Caesar and Cleopatra became the stuff of legend, shaping plays (like Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra), films, and novels. Their partnership blended realpolitik with romance, empire-building with personal desire.

Conclusion: The Woman Who Shook the Roman World

Cleopatra’s relationship with Julius Caesar was never simply about love. It was about power—how to obtain it, wield it, and survive in a world dominated by men and military might. For Caesar, the affair represented an extension of his imperial ambition. For Cleopatra, it was a bold bid to protect her dynasty and preserve Egypt’s place in a world increasingly ruled from Rome.

Though their relationship ultimately ended in tragedy, its ripple effects helped topple a Republic, birth an Empire, and etch their names forever into the annals of history.

Sources:

- Goldsworthy, Adrian. Caesar: Life of a Colossus. Yale University Press, 2006.

- Schiff, Stacy. Cleopatra: A Life. Little, Brown and Company, 2010.

- Roller, Duane W. Cleopatra: A Biography. Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Plutarch. Lives, particularly “Life of Caesar” and “Life of Antony.”

- Cassius Dio, Roman History.

Leave a comment