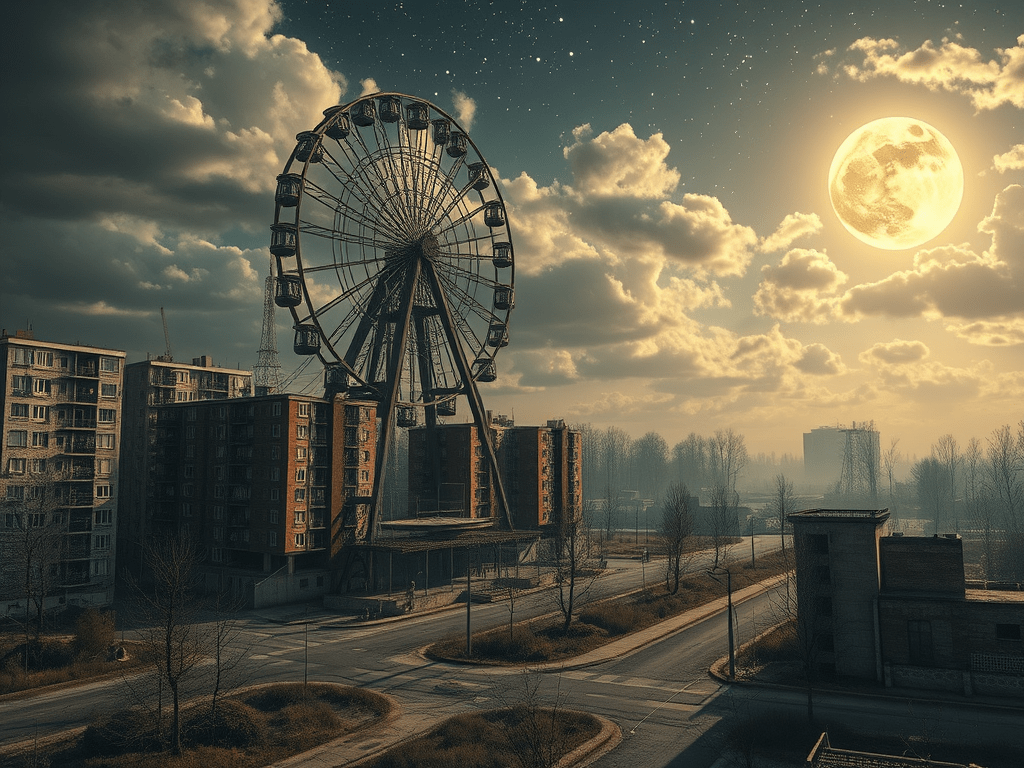

The year was 1986, and in the heart of the Soviet Union, the town of Pripyat was the shining example of the future. It wasn’t a drab, concrete sprawl; it was an atomic utopia, a vibrant, modern city built for the families of the workers at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. Young, well-educated, and confident, the 50,000 residents of Pripyat lived under the warm glow of Soviet promise. They had beautiful apartments, state-of-the-art schools, and a brand-new amusement park just waiting for its grand opening on May Day. Life was good, clean, and safe—guaranteed, they believed, by the behemoth of concrete and steel four kilometers away: Reactor No. 4.

The power plant ran on RBMK (Reaktor Bolshoy Moshchnosti Kanalnyy, or “High-Power Channel-type Reactor”) technology, a purely Soviet design that used an unusual combination of materials. Unlike Western reactors that used water as both the coolant and the moderator (to slow down neutrons), the RBMK used water for cooling but used graphite blocks—like large carbon bricks—as the moderator. This allowed it to be built cheaply and refueled while running, but it hid a terrifying secret.

The Atomic Dream Meets the Nightmare Fuel

To understand what happened at 1:23 AM on April 26, 1986, you have to understand the RBMK’s fatal flaw: the positive void coefficient.

Think of a nuclear reactor like a finely tuned engine. You need two components to control it:

- Coolant (Water): To absorb the heat.

- Moderator (Graphite): To keep the atomic reaction slow and steady.

In almost every reactor worldwide, if the cooling water overheats and turns into steam (creating a ‘void’), the reaction automatically slows down. It’s a fundamental safety feature—lose your coolant, lose your power.

The RBMK was backward. Because the graphite moderator was so efficient, if the cooling water suddenly flashed to steam, the graphite would cause the reaction to speed up dramatically. More steam meant more power, which meant more steam, creating a runaway atomic feedback loop. It was a speed pedal disguised as a safety brake. The entire design was, in essence, a catastrophe waiting for the right moment of human error.

The safety test scheduled for the evening of April 25th was supposed to be routine. The goal was to determine if a spinning turbine could generate enough power to run the emergency water pumps until the diesel generators kicked in. It was a test of the plant’s inertia—a critical safety procedure. But it was delayed by ten hours, forcing the inexperienced night shift, led by shift foreman Alexander Akimov and his young trainee Leonid Toptunov, to conduct a complex procedure they weren’t fully prepared for, under extreme time pressure and the scrutiny of Deputy Chief Engineer Anatoly Dyatlov—a man known for his brutal, unforgiving temperament.

The Ill-Fated Experiment: Bypassing Safety

The night shift was nervous. The test required the reactor to be held at about 25% power, but due to a combination of Toptunov’s inexperience and an unexpected drop, the power level plummeted dangerously low, entering a state known as the “iodine pit,” where neutron-absorbing xenon isotopes effectively poison the core. The safe reaction could no longer be sustained.

At this point, all protocols mandated the engineers to shut down the reactor completely. But Dyatlov, obsessed with completing the test, refused. He commanded them to raise the control rods—the neutron-absorbing brakes—far higher than safety rules permitted, attempting to muscle the reactor back up to the required power level. They had just 6 control rods remaining in the core—the minimum required was 30. They were running the reactor on adrenaline and pure folly, violating one safety regulation after another, including overriding the Emergency Core Cooling System (ECCS) and the Automatic Local Power Shutoff (APLS). They essentially blinded and deafened the reactor’s automated safeguards.

The reactor core, now almost fully unbraked, was struggling to generate steam. The pumps were running too fast, creating excessive vibration, and the water flow became erratic. The core was starved for stability, unstable, and ready to rebel.

The Earth Shakes: The AZ-5 Button

At 1:23:40 AM, Akimov initiated the test. The turbine steam supply was cut, the turbine began to coast down, and the operators watched their instruments. The core was running hotter, but the test was underway.

But the reactor began to surge. Akimov, seeing the power level begin to climb uncontrollably, shouted the command and slammed the AZ-5 button.

The AZ-5 was the emergency shutdown, the ultimate nuclear panic button. It was supposed to instantly drop all 211 control rods—the boron-based brakes—into the core to kill the reaction.

But the RBMK held one last, tragic surprise. To ensure the rods descended smoothly, they were fitted with short graphite tips. Graphite, remember, was the material that accelerated the reaction. As the rods dropped, those graphite tips briefly pushed aside the cooling water at the bottom of the core, creating a temporary void and a momentary spike in power, before the actual boron brakes could engage.

In the now highly unstable, low-power core, this momentary graphite spike was the final trigger. It caused an immediate, explosive flash of steam. This flash instantly triggered the positive void coefficient across the entire reactor. Akimov had hit the stop button, but the design turned it into a lethal accelerator. The power rocketed to over 100 times the reactor’s safe limit in four seconds. The sheer, violent steam pressure blew the steel channels apart, jamming the control rods a few feet in, locking the brakes in a useless position, right as the core exploded.

The reactor, the heart of the power plant, was gone. It was just a gaping, smoldering hole looking up at the stars.

Denial and Sacrifice: The First Responders

In the control room, the air was thick with smoke and confusion. Akimov, Toptunov, and Dyatlov were in denial. The seismic shock had convinced them only the water tanks had exploded. They looked at the shattered instruments and insisted the core was intact. Dyatlov, his face already flushing with radiation exposure, ordered Akimov and Toptunov to open the water valves and pump water back into the core. A futile, suicidal mission, as the core no longer existed.

But true heroism arrived moments later. The Pripyat fire department, led by Lieutenant Vladimir Pravik, was called to a “roof fire.” They had no idea they were walking into a gamma-ray inferno. They climbed to the top of the reactor building, fighting flames that were being fueled not by wood or oil, but by the burning graphite and the superheated core material.

Pravik and his men, like Vasily Ignatenko, worked tirelessly to put out the fire on the intact Reactor No. 3 next door, preventing a chain reaction of explosions. They were breathing in radioactive smoke and walking through intensely radioactive water. They reported a strange, sweet metallic taste in their mouths, and many saw a shimmering, ionizing blue glow above the reactor debris—the characteristic, deadly Cherenkov radiation. By morning, they were violently ill, their skin red and blistered, their bodies absorbing enough radiation to kill them within weeks. They were the first, tragic casualties, but their immediate sacrifice prevented the disaster from becoming an even greater catastrophe.

Meanwhile, in Pripyat, life went on. The Party officials, paralyzed by the culture of Soviet secrecy and denial, ordered a delay. It took 36 agonizing hours for the official evacuation order to be given, time enough for the children to play in the streets and for the wedding parties to finish their celebrations, all while breathing air contaminated with plutonium and Cesium-137. Only on Sunday afternoon did buses arrive, telling residents they would be gone for only three days. They left their pets, their belongings, and their entire lives behind. They never returned.

The Liquidators: A Tsunami of Heroes

The disaster response, officially handled by Moscow, became the massive, messy effort of the “Liquidators.” This was a mobilization unlike any the world had ever seen, involving hundreds of thousands of soldiers, workers, and civilians.

The initial task was to prevent a second, even larger disaster. The burning core was melting through the concrete base, and beneath it, 5,000 tons of water remained in the cooling pools. If the highly radioactive molten core reached that water, a massive steam and radioactive blast would have rendered much of Europe uninhabitable. Three plant workers—Alexei Ananenko, Valeri Bezpalov, and Boris Baranov—volunteered for a suicide mission to manually open the sluice gates in the darkness of the flooded basement. They succeeded, draining the water and averting a super-explosion. Miraculously, all three men survived.

The core itself continued to burn. Helicopter pilots flew hundreds of missions directly over the exposed reactor, dumping thousands of tons of sand, clay, lead, and boron to smother the fire and absorb neutrons. The pilots, exposed to lethal doses of radiation every time they flew through the thermal column, displayed courage beyond measure.

Perhaps the most famous—and heartbreaking—part of the cleanup involved the roof of the adjacent Turbine Hall. The explosion had scattered highly radioactive graphite chunks and core debris there. When sophisticated German and Japanese robots sent by the USSR failed almost instantly under the intense radiation, the Soviet leadership decided to use “biorobots”—literally, soldiers. Thousands of young men, many barely out of their teens, were sent onto the roof in heavy lead vests (which did little to protect their extremities) for ninety-second shifts. They sprinted across the rubble, shoveled a few chunks of graphite over the side, and then ran back. Their work was essential, but the cost was their long-term health.

Another army of Liquidators—coal miners—was drafted in from the Donbas region. They dug a 150-meter tunnel beneath the reactor to install a massive concrete heat exchanger. Working naked in temperatures exceeding 50 degrees Celsius due to the heat rising from the core, they successfully completed their task, preventing the meltdown from contaminating the groundwater.

The Long Shadow and the Sarcophagus

The world was finally forced to acknowledge the disaster two days later, not by Soviet admission, but by Sweden. On April 28th, technicians at the Forsmark Nuclear Power Plant, 1,100 kilometers away, detected unusually high radiation levels on their shoes. Tracing the radioactive cloud back to the Soviet Union, they demanded an explanation.

Under overwhelming international pressure, Mikhail Gorbachev was finally forced to break the silence, announcing the accident on state television—a revolutionary moment in Soviet history, marking the end of the totalitarian secrecy.

The immediate priority was to contain the exposed core. The solution was the “Sarcophagus,” a massive, hastily constructed concrete and steel structure built over the ruins of Reactor 4. It was an engineering marvel built under unthinkable conditions, completed in a mere 206 days by thousands of workers who knew they were shortening their lives with every swing of the hammer. The structure was never meant to be permanent, only to stabilize the ruins and contain the remaining fuel—an estimated 95% of the original core, now fused into a highly dangerous lava-like material known as “Elephant’s Foot.”

Today, Reactor 4 is covered by the New Safe Confinement (NSC), a gargantuan, movable steel arch completed in 2019, designed to last 100 years. It’s an internationally funded testament to the long-term legacy of the disaster.

Around the plant lies the Zone of Alienation, a 2,600 square kilometer area cleared of humans. Nature has aggressively reclaimed Pripyat and the surrounding area. Trees grow through the floors of apartment buildings, and wild horses, wolves, and boars roam the radioactive ghost city. While the wildlife population is thriving—an ecological paradox driven by the absence of human activity—the long-term impact on the health of the original Liquidators and the surrounding population remains a complex and tragic topic, with tens of thousands of cancer cases and chronic illnesses linked to the fallout.

Chernobyl stands as a stark, complex monument to human arrogance, systemic flaws, and breathtaking heroism. It is a story about the ghost of the atom that haunts a deserted city, reminding us that the most powerful forces are often the hardest to tame.

Sources

- Plaud, E. (2018). Chernobyl: The History of a Tragedy. Basic Books. (Considered one of the most comprehensive modern historical accounts.)

- Medvedev, G. (1991). The Truth About Chernobyl. Basic Books. (Written by a nuclear engineer and former deputy chief of the construction department at the Chernobyl station, providing early, authoritative insights.)

- International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Reports. (Official technical reports on the design, accident sequence, and immediate aftermath.)

- The World Health Organization (WHO) and UNSCEAR (United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation) reports. (Essential for long-term health and environmental impact analysis.)

Leave a comment