The Race to the Heavens: When the Sky Was the Cold War Frontier

The 1960s were a dizzying time, fueled by Cold War tension. The starting gun for the Space Race wasn’t fired by the US, but by the Soviet Union’s successful launch of Sputnik in 1957. That small satellite orbiting Earth sent shockwaves through America. It wasn’t just about showing off; it implied the Soviets could put nuclear weapons anywhere on the globe.

In response, President John F. Kennedy declared in 1961 that America would land a man on the Moon and return him safely to Earth before the end of the decade. This wasn’t a casual goal; it was a desperate national commitment. NASA’s budget exploded, soaking up nearly 5% of the entire federal budget at its peak. Tens of thousands of engineers, scientists, and technicians worked around the clock for years. The objective demanded solving problems that had literally never been conceived of before, spurring an industrial, scientific, and human effort unlike any other. They didn’t just need a bigger rocket; they needed a total paradigm shift.

Three Men and a Titan Rocket: The Crew and the Colossus

The mission, Apollo 11, required a crew of unflappable experts, each bringing a unique skill set.

- Neil Armstrong: The Commander. Cool, cerebral, and famously calm under pressure. He was a veteran test pilot who had already survived a serious accident in the fragile Lunar Landing Training Vehicle. His quiet focus was exactly what the mission demanded.

- Buzz Aldrin: The Lunar Module Pilot. A brilliant engineer with a Ph.D. from MIT, his deep understanding of orbital mechanics and rendezvous procedures was essential for navigating the complex docking maneuvers in lunar orbit. He brought technical genius and unwavering discipline to the cockpit.

- Michael Collins: The Command Module Pilot. Dubbed “The Loneliest Man in History,” Collins’s task required immense precision and psychological resilience. His critical job was to remain in the Command Module Columbia, orbiting the Moon. For 21 hours, he was entirely cut off from radio communication for 48 minutes of every orbit as he passed over the far side of the Moon—a silent, solitary vigil. If Armstrong and Aldrin failed to ascend, he would have no choice but to fly home alone.

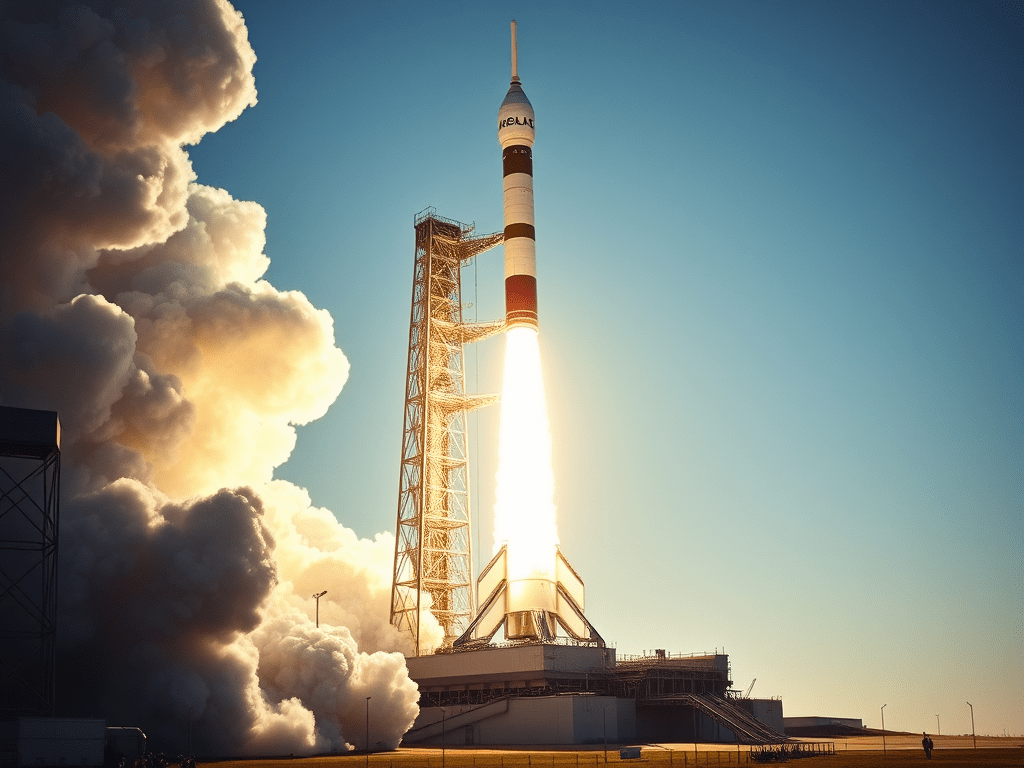

Their ride was the Saturn V—a gigantic, three-stage monster. Think of it as a skyscraper designed to leave the atmosphere. It stood taller than the Statue of Liberty (363 feet) and weighed over 6 million pounds. On July 16, 1969, it stood ready at Launch Complex 39A in Florida, poised to burn more than 4 million pounds of fuel in just the first few minutes of flight.

Launch and the Silent Cruise: Breaking Free of Earth’s Grip

At 9:32 a.m. EDT, the launch sequence began. The five colossal F-1 engines on the first stage roared to life, generating a staggering 7.5 million pounds of thrust. The sheer noise shook the ground for miles, and those watching felt the rumble deep in their chests. Slow and deliberate, the Saturn V lifted off, climbing for 2 minutes and 42 seconds before the first stage ran dry and detached. Two more powerful stages fired in succession until the crew reached Earth orbit.

After a brief check, the final engine burn—the Trans-Lunar Injection (TLI)—kicked them onto a trajectory toward the Moon. The crew spent three days crossing the nearly 240,000 miles. It was a journey of profound solitude, broken only by the crackle of Houston radio and the gentle hum of the spacecraft Columbia. As they executed the critical maneuver to turn the command module around and dock with the Eagle, the Earth began to shrink. When they finally passed into the Moon’s shadow, the Earth became a distant, fragile blue marble—a view that filled them with an overwhelming sense of awe and responsibility.

The Descent: The Overloaded Brain, the Heroic Fix, and the Empty Tank

On July 20, the moment of truth arrived. Armstrong and Aldrin climbed into the Lunar Module (LM), nicknamed Eagle. They separated from Collins in the Columbia and began their perilous powered descent toward the Sea of Tranquility.

It was immediately fraught with peril.

First, the onboard computer began spitting out alarming 1202 and 1201 error codes. The computer, programmed by a team led by the brilliant Margaret Hamilton, was acting like a person trying to do too many things at once—it was overloaded. For a terrifying moment, the landing seemed scrubbed. But in Houston, 26-year-old guidance officer Steve Bales (with confirmation from flight controller Charlie Duke) calmly determined that the system was smart enough to shed the non-essential tasks and prioritize the critical landing functions. They were “Go on that.” Bales would later receive the Presidential Medal of Freedom for this split-second decision.

Next, as Armstrong peered out the window at 500 feet, he realized the auto-pilot was aiming for a debris-strewn crater the size of a football field. With only seconds to spare, he took manual control, flying the Eagle horizontally over the hazardous terrain like a helicopter. The descent rate was too fast, the lunar dust was blinding, and the fuel warning light came on.

- Mission Control: “30 seconds!” (Fuel remaining—the absolute minimum, past which the mission rules said they must abort)

- Armstrong: “Picking up some dust… Base contact light.”

With just 17 seconds of fuel remaining—barely a single deep breath—the Eagle settled gently onto the lunar surface.

Tranquility Base: A Giant Leap for Humankind

The tension broke. A relieved Armstrong transmitted the most famous, and most understated, words of the mission: “Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.”

About six hours later, after depressurizing the cabin, Armstrong backed out onto the ladder. The live feed was grainy, but the world was silent, watching. At 10:56 p.m. EDT on July 20, 1969, he put his left boot down on the dusty lunar surface. He followed his steps with the iconic line, intending to say, “That’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.” (The “a” was lost in transmission, but its intent remains clear.)

Buzz Aldrin soon joined him, famously describing the lunar landscape as “magnificent desolation.” They spent two and a half hours outside, collecting 47 pounds of rock and soil samples, deploying scientific instruments (including a solar wind collector and a seismometer), and planting the American flag. The ascent was brief and successful, lifting the Eagle’s upper stage off the Moon and successfully docking with Michael Collins.

The Legacy: From Space to Everyday Life

The safe return of Apollo 11 to Earth was met with a global ticker-tape parade of celebration. It was proof that humanity could set its sights on an almost unimaginable goal and, through ingenuity, dedication, and incredible personal bravery, achieve it.

The long-term impact of Apollo extended far beyond space. The drive to miniaturize technology for the cramped spacecraft led directly to the development of microchips, integrated circuits, and advanced computing techniques that underpin today’s smartphones and computers. It inspired an entire generation of scientists and engineers, and cemented the idea that no problem is too large to solve. The feat transcended politics; it was a human moment—a shared testament to our boundless potential, forever etched in the annals of time.

Sources

- Chaikin, Andrew. A Man on the Moon: The Voyages of the Apollo Astronauts. Penguin Books, 1994.

- NASA History Division. Apollo 11 Mission Overview. (Various official documentation).

- The transcripts of the Apollo 11 mission communications between the crew and Mission Control.

Leave a comment