December 1776. The year had been a catastrophe for the American cause. The grand, noble words of the Declaration of Independence, penned just months earlier, seemed like a cruel joke now. Defeats had stacked up like kindling—Long Island, White Plains, Fort Washington—and General George Washington, Commander-in-Chief of the fledgling Continental Army, had been chased across New Jersey like a fox by the British hunting dogs.

The army, reduced to a desperate few thousand men, was a shadow of its former self. Their uniforms were rags, many men had no shoes, and the trail they left across the frozen ground was sometimes stained with blood from frostbite. Most crucially, the enlistment terms for many soldiers were due to expire on December 31st. Without a victory, the army—and perhaps the entire Revolution—would simply dissolve into the bitter winter air.

“The game is pretty nearly up,” Washington himself had written. Desperation was a commander’s greatest weakness, but sometimes, it is also the sharpest spur.

Across the Delaware River in Trenton, New Jersey, were the enemy: a garrison of roughly 1,500 highly disciplined German mercenaries from Hesse-Kassel, whom the Americans called “Hessians.” They were formidable, professional soldiers, and they felt comfortably secure. Who would dare attack in such a storm? On Christmas?

Washington, the man of quiet dignity and intense resolve, knew exactly who.

The Crossing: Victory or Death

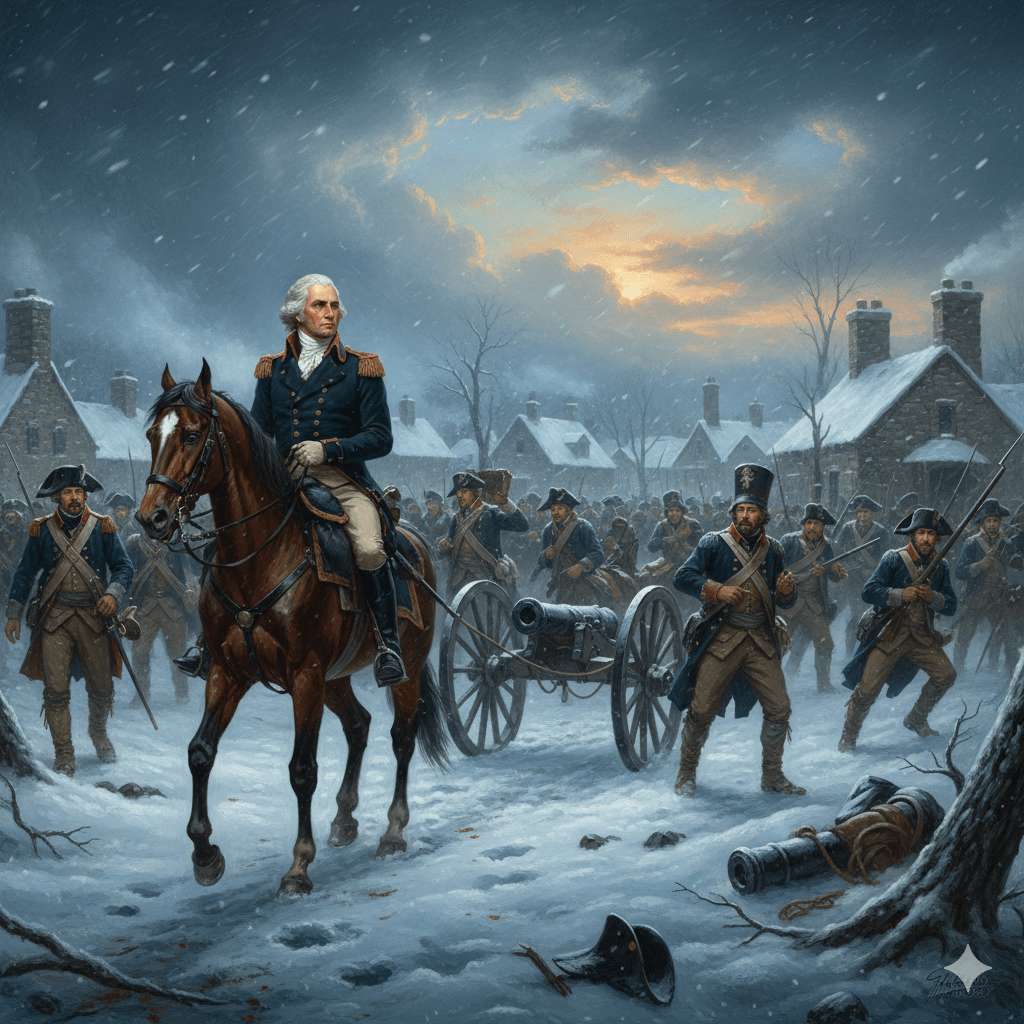

Washington’s audacious plan was simple in its objective and terrifying in its execution: cross the ice-choked Delaware River on Christmas night, endure a nine-mile march, and launch a surprise dawn attack on the Hessian garrison in Trenton. The password for the night was a testament to the stakes: “Victory or Death.”

The Unstoppable Rivermen

The key to the whole operation lay in the hands of one man: Colonel John Glover of the 14th Continental Regiment, a former Marblehead fisherman. His men, hardened by a lifetime spent battling the turbulent Massachusetts coast, were the only ones capable of ferrying an entire army across a raging, freezing river. They were masters of the Durham boats—long, heavy-duty cargo vessels with a shallow draft, perfect for ferrying horses and artillery.

The crossing, scheduled to begin at dusk on December 25th, was immediately swallowed by a fierce Nor’easter. Freezing rain turned to sleet, and then a thick, driving snow. The river, already clogged with dangerous chunks of ice, became a churning, white nightmare.

Brigadier General Henry Knox, Washington’s enormous and perpetually jovial Chief of Artillery, wrote: “The floating ice in the river made the labor almost incredible.” Every stroke of the oar, every shift of a cannon, was a fight against nature.

The General’s Stare

The troops gathered on the Pennsylvania shore were a sorry sight. Wet, miserable, and shivering, they had endured one hellish year and now faced an ordeal that seemed suicidal. Many read or heard portions of Thomas Paine’s new pamphlet, The American Crisis, which contained the immortal opening: “These are the times that try men’s souls.”

General Washington, a monument of resolve astride his horse, was everywhere. Tall, with a solemn expression that rarely cracked, he surveyed the chaos. His presence was the only thing holding the endeavor together. He didn’t rant or rave; he simply willed them forward. The sheer impossibility of the task made the men work harder.

The planned pre-dawn attack was delayed by a catastrophic three hours. Instead of finishing the crossing by midnight, the last of the 2,400 men and 18 precious pieces of artillery were not ashore in New Jersey until 2:00 a.m. The brutal march to Trenton would begin in the darkness, and they would be fighting in full daylight. The element of surprise was hanging by a thread of sleet.

Colonel Rall: The Ill-Fated Commander

While Washington and his army struggled through the storm, the man in charge of Trenton, Colonel Johann Gottlieb Rall, was secure in his quarters. Rall was an experienced, brave, and well-liked commander, but he possessed a fatal flaw: overconfidence mixed with a disdain for the American “country bumpkins.”

Rall and his 1,500 Hessians—the Regiments Rall, Lossberg, and Knyphausen—had settled into Trenton for comfortable winter quarters. The town, a small community of about 100 houses, was secured by outposts on the main roads, but Rall refused to build permanent defenses like trenches or redoubts, allegedly stating:

“Let them come! We will go at them with the bayonet!”

A Fateful Warning

Rall’s overconfidence led to tragic negligence. American loyalists, seeing the activity on the other side of the river, had tried to warn him. One of the most famous anecdotes involves a Tory farmer who brought Rall a letter on the evening of December 25th, detailing the American plans. Rall was supposedly engaged in a night of card-playing, drinking, and merry-making, having just celebrated a German Christmas.

Tired of the interruption, Rall impatiently stuffed the unopened note into his coat pocket. He would never read it. While historians now debate the severity of Hessian drunkenness (eyewitness accounts suggest the fighting men were largely sober), Rall’s dismissiveness of intelligence proved a far greater danger.

The March: Cold, Snow, and Resolve

At 4:00 a.m., two American columns began the harrowing, nine-mile march toward Trenton.

- Right Wing: Led by Major General Nathanael Greene, and personally accompanied by Washington and General Knox, this column took the inland Pennington Road.

- Left Wing: Led by Major General John Sullivan, this column followed the River Road.

The storm had not abated. One soldier described the air as “extremely cold and snowy.” The men struggled through the snow and sleet, their threadbare clothing offering little protection. The constant scraping of ice and frozen water on their clothes was the only sound besides the measured, grim tramp of boots.

Washington rode among the troops, urging them on. At one point, he was heard to say, to the nearly fainting men:

“Press on, press on, boys!”

The troops were exhausted, but as they neared Trenton, their sense of desperate purpose returned. They knew what was at stake.

Artillery and the Future President

The artillery under Henry Knox was crucial. He had the difficult job of dragging 18 heavy cannons through the snow. Knox’s guns would be strategically placed at the top of the two main streets—King and Queen Streets—to form a devastating blockade and clear field of fire.

Among Greene’s column was a young Lieutenant named James Monroe (the future fifth U.S. President), who commanded a small advanced unit. They were the first to make contact with a Hessian outpost.

The Battle: A Raging Fire for an Hour

Just after 8:00 a.m. on December 26, 1776, Washington and his two divisions converged on the north and west sides of Trenton, achieving the complete surprise he had gambled everything on.

“Der Feind! Der Feind!”

The first real alarm came from the outpost on Pennington Road. Lieutenant Andreas von Wiederholdt, a Hessian officer, stepped out for a breath of fresh air and was met by a barrage of American musket fire. He instantly recognized the threat, crying out, “Der Feind! Der Feind!” (The Enemy! The Enemy!)

The Hessians, scrambled out of their barracks into the blinding snow. They were instantly disorganized, having to form ranks in the main streets while Washington’s two columns flooded the town from opposite sides.

The Shotgun Wedding of King and Queen Street

Knox’s artillery immediately went to work. The Americans had secured the high ground at the intersection of King and Queen Streets, effectively turning the two main thoroughfares into deadly kill zones. As the Hessian companies poured out of their quarters, they were met with a storm of grapeshot and cannonballs raking the street.

The discipline of the Hessians, their great strength, now became a weakness. They were trained to fight in open-field formations, not in urban, close-quarters chaos. Rall’s men tried to counter-attack and reclaim their field artillery, but the American position was too strong.

Colonel Rall himself, finally roused and on horseback, fought bravely to rally his disordered troops. He was a target. Charging an American unit, he was struck by two musket balls and fell mortally wounded from his saddle.

The Surrender

With their commander down, the remaining Hessians were leaderless, confused, and surrounded. Major General Sullivan’s wing, which had come in along the river, had successfully cut off the main escape route across the Assunpink Creek bridge, forcing the remaining troops back into the northern part of the town.

Out of options, the remaining Hessians—nearly 900 men—were forced to surrender in a frozen peach orchard east of Trenton. The entire battle had lasted barely an hour.

The Aftermath: A Morale Lifeline

The sheer scale of the American victory was staggering and disproportionate.

- Hessian Losses: 22 killed (including Colonel Rall), 83 wounded, and approximately 900 captured. The Americans also seized an immense store of muskets, bayonets, swords, and 6 desperately needed cannons.

- American Losses: Two men died from exposure during the march, and only five were wounded (including young Lieutenant Monroe, who suffered a severe shoulder wound).

Washington’s immediate decision was to retreat back across the Delaware with his prisoners and spoils. His army was exhausted, his two supporting divisions had failed to cross the river, and a major British force was nearby. The Continentals had fought for 36 hours straight, and the mission—a lightning-fast blow—was complete.

The Phoenix Rises

The Battle of Trenton did not win the American Revolution, but it was the lifeline that saved it. The victory, combined with the subsequent success at Princeton a week later, achieved four crucial things:

- Morale: The victory was a massive psychological boost. A beaten, despairing army had defeated a professional European force. The “fox” had finally bitten back.

- Recruitment: It inspired new enlistments and, crucially, convinced veteran soldiers whose terms were expiring to re-enlist, often for a $10 bounty. The Continental Army would live to fight another year.

- Supplies: The captured food, blankets, and weapons kept the army functioning through the darkest parts of the winter.

- Washington’s Legend: It solidified George Washington’s reputation as an ingenious and determined military leader. He had taken a desperate gamble, and it paid off handsomely.

The Christmas miracle was not a sudden act of fate, but the culmination of extraordinary human endurance, strategic genius, and a powerful refusal to admit that the game was, in fact, up.

Sources

- Fischer, David Hackett. Washington’s Crossing. Oxford University Press, 2004. (Highly recommended for detailed narrative.)

- American Battlefield Trust. Trenton – December 26, 1776. (For key figures and battle maps).

- Leutze, Emanuel. Washington Crossing the Delaware (1851). (A famous, if historically inaccurate, artistic depiction that cemented the event’s legend).

- Washington, George. Letter to John Hancock, December 27, 1776. (Primary source document detailing the immediate aftermath).

Leave a comment