Did you know that the man who won re-election in 1916 on the very specific, very loud slogan “He Kept Us Out of War” asked Congress to declare that exact war just a month after his second inauguration?

History often looks inevitable in the rearview mirror, but the entry of the United States into World War I was anything but. It was a messy, agonizing, three-year saga of diplomatic tightrope walking, moral outrage, economic entanglement, and a piece of spy craft so audacious it sounds like a rejected James Bond script.

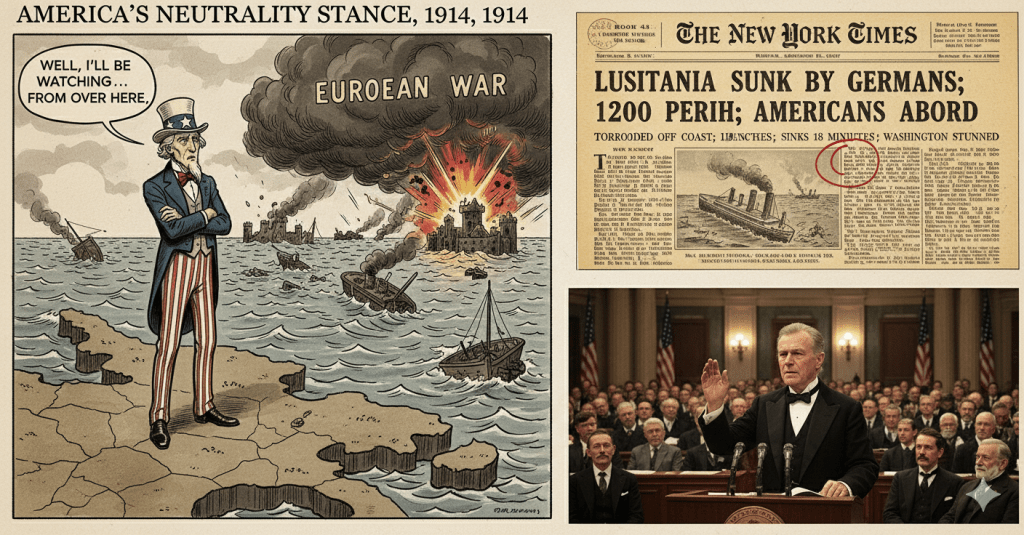

In 1914, when the powder keg of Europe erupted, the average American looked across the Atlantic with a mixture of horror and relief. It looked like the apocalypse, but thankfully, it was their apocalypse. The United States was a developing industrial giant, content in its hemisphere, with an army smaller than Portugal’s and a firm desire to mind its own business.

So, how did a fiercely neutral nation end up sending two million “doughboys” into the meat grinder of the Western Front? It wasn’t one single event, but a slow-burning fuse lit by technology, economics, and a catastrophic German gamble.

The Great American Melting Pot (and Boiling Pot)

When war broke out in August 1914, President Woodrow Wilson—a scholarly, slightly aloof idealist—issued an immediate declaration of neutrality. He urged Americans to be “impartial in thought as well as in action.”

This was easier said than done. The United States in 1914 was a demographic powder keg. Of the 92 million people living in the U.S., roughly one-third were either born abroad or had at least one foreign-born parent. Millions of German-Americans naturally sympathized with their ancestral homeland. Millions of Irish-Americans hated Great Britain with a burning passion and certainly didn’t want to fight to save the British Empire. Conversely, the “Old Stock” American elite felt a deep cultural and linguistic kinship with Britain and France.

Wilson’s neutrality wasn’t just a preference; it was a necessity to keep the country from tearing itself apart. If he chose a side, he risked a civil war at home while trying to fight one abroad.

The “Silent Partner”: Economics of Neutrality

While officially neutral, America was very much open for business. Initially, the U.S. was in a recession, but European war demands turned into an economic bonanza. The catch? The British Royal Navy had immediately established a blockade of Germany. Therefore, American “neutral” trade was overwhelmingly one-sided.

American farmers fed Allied soldiers, and American factories—like Bethlehem Steel and DuPont—built Allied munitions. American banks, led by the titan J.P. Morgan, loaned billions of dollars to Britain and France to pay for these goods. By 1916, American prosperity was inextricably linked to an Allied victory. If Britain and France collapsed, the American economy would likely follow them into the abyss. Germany, observing this, didn’t see a neutral nation; they saw America as the Allied powers’ silent, wealthy partner.

Terror Beneath the Waves: The Lusitania

World War I introduced terrifying new technologies—poison gas, tanks, airplanes—but for the United States, the most consequential was the Unterseeboot, or U-boat.

Germany, strangled by the British naval blockade and unable to match Britain’s surface fleet, turned to submarine warfare. The submarine, by its nature, couldn’t follow the old “cruiser rules” of warfare. Those rules dictated that a warship must hail a merchant vessel, check its cargo, and allow the crew to safely abandon ship before sinking it. A fragile U-boat that surfaced to do this would simply be blown out of the water by armed merchant ships.

Instead, U-boats attacked without warning, from beneath the waves. To Americans, this wasn’t war; it was piracy.

The first major shock came on May 7, 1915. The British ocean liner RMS Lusitania—the Concorde of its day, carrying wealthy socialites, businessmen, and families—was torpedoed off the coast of Ireland. It sank in just 18 minutes. Of the 1,198 people who drowned, 128 were Americans.

The American public was enraged. Former President Teddy Roosevelt demanded war, calling it “murder on the high seas.” However, Wilson kept his cool. He famously stated there was such a thing as a man being “too proud to fight.” He hammered Germany with diplomatic notes, and terrified of bringing America into the war, Germany issued the “Sussex Pledge” in 1916, promising to stop sinking non-military ships without warning. The crisis abated, and Wilson rode that wave of diplomatic success straight to his 1916 re-election.

The Most Audacious Blunder: The Zimmermann Telegram

By early 1917, the war in Europe was a bloody stalemate. Germany was starving due to the British blockade. The German High Command realized they could not win a long war of attrition. They needed a knockout blow.

On January 31, 1917, Germany announced they would resume unrestricted submarine warfare. They knew this would likely bring the U.S. into the war, but they gambled that they could starve Britain into surrender before the “unprepared” Americans could arrive.

But they needed a plan to keep the Americans busy at home. This is where the story gets wild.

In late February 1917, British intelligence handed Wilson a bombshell: an intercepted and decoded telegram from German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmermann to the German minister in Mexico.

The content was staggering. It proposed a military alliance between Germany and Mexico. If the U.S. entered the war, Germany promised Mexico financial support and, crucially, help in reconquering its “lost territory” in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona.

The Zimmermann Telegram (Decoded Excerpt): “We make Mexico a proposal of alliance on the following basis: make war together, make peace together, generous financial support and an understanding on our part that Mexico is to reconquer the lost territory in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona.”

For Americans in the landlocked Midwest or West, submarine warfare had felt abstract. But a German plot to invade Texas? That was a direct threat to the homeland. It sounded like a British forgery—until Arthur Zimmermann, in an act of inexplicable honesty, publicly admitted he sent it. The telegram acted as a chemical catalyst. It bridged the gap between the pro-war East Coast and the isolationist interior. Germany had managed to alienate every corner of the United States simultaneously.

Crossing the Rubicon: “The World Must Be Made Safe for Democracy”

Throughout March 1917, German U-boats made good on their threat, sinking several unarmed American merchant ships. The patience of the American people, and their President, had run out.

On the rainy evening of April 2, 1917, Woodrow Wilson was driven to the Capitol building to address a joint session of Congress. The atmosphere was electric. Cavalry troops patrolled the streets, fearing German sabotage.

Wilson, the man who had tried so hard to stay neutral, delivered a somber but soaring speech that redefined American foreign policy for the next century. He did not ask to fight for territory, or for revenge, or even just for free trade. He reframed the conflict as a great moral crusade.

“The world must be made safe for democracy,” Wilson declared. He painted the German autocracy as a menace to civilization itself. He asked Congress to declare war not to destroy Germany, but to bring peace and safety to all nations and make the world itself at last free.

Four days later, on April 6, 1917, the United States formally declared war. The vote was not unanimous. In the House, 50 representatives voted no, including Jeannette Rankin of Montana, the first woman ever elected to Congress. “I want to stand by my country, but I cannot vote for war,” she said.

The irony was palpable. The nation was entirely unprepared. The U.S. Army was the 17th largest in the world, smaller than the army of Romania. They had virtually no tanks, few airplanes, and not enough machine guns. But the sleeping giant had finally awoken.

Why This Still Matters

The entry of the U.S. into World War I is arguably the most significant turning point in modern American history. Before 1917, the U.S. was a regional power, adhering largely to George Washington’s old advice to avoid “entangling alliances” in Europe.

- The Birth of a Superpower: April 6, 1917, was the birth certificate of the “American Century.” It was the moment the U.S. stepped onto the world stage as a global power, accepting a self-appointed role as the defender of international order.

- Wilsonian Idealism: The idea that American military power should be used to spread democracy and human rights—rather than just for territorial gain—became the template for American foreign policy from World War II to the Cold War and beyond.

- The Unintended Consequences: The way the war ended (and the U.S.’s subsequent retreat into isolationism in the 1920s) sowed the seeds for the even greater catastrophe of World War II just two decades later.

By entering “The War to End All Wars,” America changed its DNA forever. We stopped being a nation that looked inward and started being the nation the rest of the world looked toward—for better or for worse.

Sources

- Berg, A. Scott. Wilson. G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 2013.

- Doenecke, Justus D. Nothing Less Than War: A New History of America’s Entry into World War I. University Press of Kentucky, 2011.

- Kennedy, David M. Over Here: The First World War and American Society. Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Tuchman, Barbara W. The Zimmermann Telegram. Viking Press, 1958.

- The Library of Congress. “World War I: Primary Documents on Events from 1914 to 1919.”

Leave a comment